Macro utopia

Our first soft landing?

First a bit of throat clearing:

The concept of a soft landing is a bit ambiguous. Reasonable people might disagree with my take on the current situation.

I recognize that this is a weird time to claim success, as many people fear a near-term recession due to the trade war. I’m agnostic on whether a recession will occur in 2025, but even if it does, I believe it’s useful to take stock of the current state of the economy at this interesting moment in time.

Because I’ve recently attracted many new readers, in the first part of this post I’ll review my previous arguments about the weird absence of soft landings and mini-recessions in the US business cycle. Then, in the second part of the post I’ll discuss the past 5 years.

Part I: The US is weird

The US has a weird business cycle. You might expect occasional recessions, followed by recoveries, followed by extended periods of normal times (say at least three years). Lots of other countries see this sort of pattern. But we’ve never experienced this pattern without seeing a surge in inflation. In almost every case, the economy slips into recession almost as soon as the unemployment rate stops falling. Until now . . .

You might also expect mini-recessions to be much more common that bigger recessions, just as small earthquakes are much more frequent than big earthquakes, or individual murders are far more common than mass murders. Many other countries do experience mini-recessions. But the US has never had one, not once. At least not if you define a mini-recession as a period where the unemployment rate rises by between 1.0 percent points and 2.0 percentages points from the cyclical low, and then begins falling again.

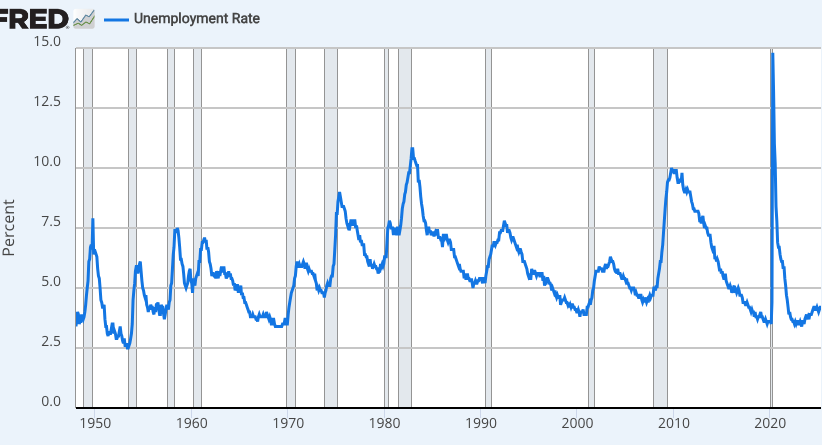

As is often the case, a picture makes these points easier to see. (You can expand the graph to get a clearer look):

In each recession (grey bars), the unemployment rate rises more than 2.0% from the previous cyclical low, although in some cases not peaking until early in the next expansion. You don’t see the unemployment rate rise by 1.0%, or 1.5%, or 2.0% and then start falling again. No mini-recessions.

There was one previous case where the economy continued expanding for more than three years after unemployment fell to a very low level, but this period (1966-69) saw a major surge in inflation. In an ideal soft landing, unemployment would fall to near cyclical lows, and stay there for years without a major surge in inflation.

I’ve always viewed this pattern as being deeply weird, partly because I’d expect mini-recessions and soft landings to occur on occasion, and partly because other countries do experience these outcomes. Why is the US so unusual?

[As an aside, this weird pattern is what causes the famous Sahm’s Rule to be so effective for the US. As far back as 2011, I argued that recessions always occurred when the unemployment rate rose at least 0.6% from the cyclical low. But both my rule and Sahm’s Rule were broken in the recent expansion, as the unemployment rate rose by 0.8% with no recession. Not even a mini-recession.]

Part II: How did we achieve a soft landing?

In the late 2010s, I was optimistic that the US was about to have its first soft landing. I still believe we would have done so if not for Covid. After Covid, I became very pessimistic, wondering if I’d even live long enough to see our first soft landing. But the recovery from Covid turned out to be quicker than almost all economists not named Lars Christensen expected, and unemployment fell to 3.7% by March 2022. Of course the quick recovery was partly due to excessive stimulus (both monetary and fiscal). But then we got another surprisingly good outcome; the high inflation was brought down without a recession (so far).

In this cycle, the very lowest unemployment rate was reached in April 2023 (at 3.4%), and yet 24 months later we are still not in recession (as 177,000 jobs were created last month.) Previously, we’d never gone more than 16 months without recession after unemployment hit the cyclical low.

And so here we are. In March, 12-month PCE inflation was only 2.3%, not far above target. Unemployment has nudged up to 4.2%, but that’s still a relatively low level. It seems like we have a soft landing—the best macroeconomic outcome in American history. Of course almost no one feels that way. MAGA types believed the Biden economy was horrible, and Democrats fear that Trump is currently wrecking the economy.

Biden really did over-stimulate the economy and create excess inflation, and Trump’s trade war really does threaten the economy (although recent news suggests he’s backing off, perhaps because of worry that tariffs might trigger a recession.) But if you set aside politics for the moment, it really is true that the Fed seems to have achieved America’s first soft landing, or at least something close (if you wish to quibble that 2.3% inflation is not 2.0% inflation.)

So how’d they do it? How did the Fed bring inflation down without triggering a recession? I see three factors:

Fed credibility kept wage inflation somewhat under control.

The immigration surge was a positive supply shock.

NGDP growth has been brought down gradually.

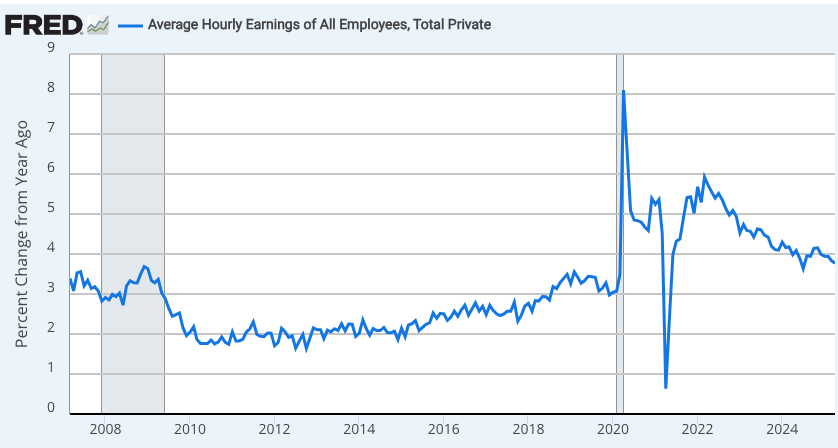

Let’s take them one at a time. Here is 12-month growth in average hourly earnings:

In 2007 and again in 2019, wage growth was in the 3.0% to 3.5% range, which is normal for a full employment economy with a 2% price inflation target. Ignore the low wage inflation of the early 2010s, which was caused by the Great Recession. Also ignore the spike up in 2020 and the spike down in 2021; those are an artifact of “composition effects”. Even if the wage of no individual worker changes, average wages during a period like Covid would spike up as lots of low paid service workers get laid off, and vice versa after Covid.

Instead focus on how the excessive stimulus of 2021-22 led to a peak in wage inflation of 6.0% in the middle of 2022. That is the inflation that the Fed had to bring back to around 3.0% to 3.5%, by gradually slowing the growth rate of NGDP. And so far (knock on wood), they’ve done so. Nominal wage inflation over the past 12 months still runs at almost 3.8% (a bit too high), but it’s only 3.3% over the past 6 months, 2.6% over the past 3 months, and 2.0% over the past month. We’re almost there.

Our textbooks describe the Phillips Curve in terms of price inflation and unemployment, but Phillips himself used wage inflation, and that is the correct variable to focus on. The essential macroeconomic problem is that nominal wages are sticky and therefore fluctuations in NGDP growth tend to lead to fluctuations in employment and output. It’s that simple.

The Fed also got lucky in a couple ways. Decades of relatively low inflation made younger workers forget the 1970s. The price spike of 2021-23 was viewed as being at least somewhat transitory, and thus wage inflation didn’t rise by quite as much as price inflation or NGDP growth. But another big factor was the immigration surge, which provided some badly needed additional labor when the economy was overheating due to excessive demand stimulus.

I don’t wish to debate immigration in this post. It’s perfectly understandable to be outraged about the immigration surge because of concerns about the rule of law or the impact on our culture. That’s another debate. But in pure macroeconomic terms the immigration surge was a major contributor to the US economy’s strong performance in the early 2020s. By restraining nominal wage growth, immigration made it much easier to bring inflation down without triggering a recession.

To summarize, the Fed got lucky with immigration, but it also burned up some of its credibility capital (which might hurt it next time.) The Fed also did a genuinely good job of gradually slowing NGDP growth. Luck and skill. Yes, my usual mealy-mouthed, “on the one hand, on the other hand” analysis. Sorry.

In my first post after Liberation Day, I began with the following observation:

The tariffs will likely be scaled back. I will discuss the impact of the proposed tariffs, but these should NOT be viewed as unconditional forecasts of their impact on the economy. (FWIW, markets seem to expect a bit of stagflation.)

And I’ve repeated that warning in subsequent posts. Today, I believe my caution is looking pretty good.

In the weeks prior to Liberation Day, markets seemed to believe that the Trump trade policy was sort of bad, but that there was a Trump put. Then for a while investors thought “Oh my God! Maybe Trump is serious.” Now they are back to thinking that Trump’s trade policy is sort of bad, but there is a Trump put. They think he’ll back off somewhat—perhaps to 10% tariffs.

Of course even this take is provisional, and may look foolish in another few weeks.

Part III: Lessons from the soft landing

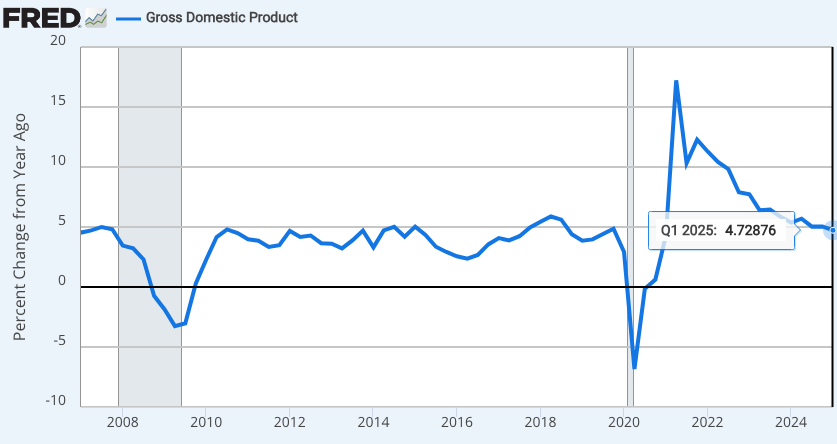

So what lesson can we learn from this soft landing? Nothing that we should not have already known, except for the fact that Americans pay no attention to the rest of the world. Australia recently went 29 years without recession, and would have gone even longer if not for Covid. Britain had a soft landing in the early 2000s. Periodic recessions are not inevitable—they are mostly caused by nominal shocks, i.e., bad monetary policy. Covid is the exception, not the rule. Even the Great Recession of 2008 was caused by a huge plunge in NGDP growth, from positive 5% to negative 3%.

Not only are recessions not inevitable, they are not desirable. They certainly do not represent the economy cleansing itself of “excesses”. If we really do engage in excesses, the appropriate punishment is a boom—i.e., everyone should knuckle down and work harder.

With sound monetary policy, it would be possible to keep NGDP growth close to 4%, particularly if we did level targeting. We are not there yet, but we are getting closer. And I would stand by that claim even if a trade war pushes us into a mild recession in 2025. Trump’s policy is the worst macroeconomic policy mistake by a president that I’ve seen in my lifetime, and yet it is still not clear that it will cause even a mild recession.

There’s a great deal of ruin in a nation. — Adam Smith

PS. I recently told commenters that I wasn’t sure if we’d achieved a soft landing. Today’s employment report (especially the very low wage inflation), finally nudged me over the line. But it’s a judgment call.

I'll offer up a half baked and probably unoriginal theory that the U.S. has a different track record of unemployment cycles and recessions because we don't have a cohesive political economy. Yes, we have a common currency, an active central bank, and a strong federal government but regional differences are more profound than these unifying factors. I bet that an analysis of the unemployment rate and per capita economic output of our five largest states over a timespan of 40 years would reveal that they have outperformed the bottom twenty states by a significant margin. Consequently, prosperity of the big states is more persistent over time---California is rich and gets richer while Alabama stays poor. When we've had national recessions California experiences less pain while Alabama gets punched in the face.

I think this explains in part the success Trump has enjoyed in the geographic middle of the country. People in the rural areas and 2nd tier cities of those states have experienced hard landings more frequently and more severely than in larger cities.

"If we really do engage in excesses, the appropriate punishment is a boom—i.e., everyone should knuckle down and work harder."

Sumner, how would you have created a boom in the Soviet transition to capitalism, c. 1990?