Modeling inflation dynamics

With a model that doesn't look like a model

I recently spent the greater part of a day writing a long point-by-point rebuttal to Tyler Cowen’s recent critique of my work. At the end, I decided that this is the wrong approach. Arguments are rarely helpful. I need to write a post better explaining my approach to monetary economics.

It isn’t just Tyler, most economists who have bothered to look at my work don’t really understand what I’m doing. It’s only human to think, “Poor, poor pitiful me, always so misunderstood.” But many of these economists are clearly smarter than me. If I’m being widely misunderstood, that’s on me.

So I (metaphorically) tore up the post and decided to start over. This will be a bit long, so I’ll start with a few general guideposts. I hope that you’ll see that I actually am responding to Tyler—not so much point by point, rather by better explaining my approach.

Here are a few guideposts, in case you get lost:

Macroeconomics should be more like finance, less like engineering.

Macroeconomic prediction is often difficult, if not impossible.

Macroeconomic explanation is often possible (ex post), but the best explanations won’t even look like explanations to the average person, even the average economist. A “model” need not be a set of equations.

Macro models of inflation and business cycles should be focused on the role of policy mistakes.

A possibly helpful analogy: Richard Rorty was also misunderstood. He was viewed as denying truth, whereas he was actually denying the usefulness of the field of epistemology, denying that there was a one-size-fits-all theory of what constitutes truth. My work is a critique of standard macro methodology.

Part 1: Prediction and explanation

Five years ago, I did not predict the sharp run-up in the price of Nvidia stock. Nor did I predict the sharp rise in Bitcoin prices.

Today, I believe that I can provide a plausible explanation for the rise in Nvidia stock, as their chips are especially useful in the booming AI field. On the other hand, I don’t believe I can provide a useful explanation for the rise in Bitcoin prices. Even if I’d had a crystal ball back in late 2019, and could see how all the “fundamentals” of the global economy would evolve over the next 5 years, I would not have predicted Bitcoin to reach $100,000.

From these two examples, we can see that:

Prediction is really hard.

Ex post explanation is easier than prediction.

Even ex post explanation may be difficult in some cases.

Now let’s think about how prediction and explanation applies to the path of US inflation over time. Back in 2004, if you asked an economist to predict the average inflation rate over the next 20 years, they probably would have picked a figure close to 2%, which even then was viewed as the Fed’s (unofficial) target for PCE inflation. Actually, inflation has average 2.2% over the past 20 years—not too bad! (TIPS spreads were also in that ballpark.)

But of course there’s the joke about the guy who drowned in a lake with an average depth of 4 feet. We’ve had some undesirable changes in (PCE) inflation, from near zero at times in 2009, to a peak of about 7% in 2022. Those movements in inflation have been largely unanticipated. Can we now explain that variation? I’ll return to that question later, but first let’s think about how inflation has changed over longer periods of time.

Suppose that you interviewed an economist back in early 1933, and asked him to predict the price level 100 years into the future. He might have thought to himself “Hmm, prices are about the same today as they were when the country was founded 150 years ago, so I’ll predict roughly the same price level 100 years into the future. That would have been a reasonable assumption.

Actually, today’s price level is already about 24-fold higher than in 1933. Not 24% higher, 24-fold higher. That’s a big miss. On the other hand, it would be easy for a visitor from the future to give an explanation for that increase that the 1933 economist would easily comprehend. Even in 1933, economists understood the potential impact of switching from gold to fiat money. Of course that explanation would only go so far. Printing lots of fiat money gives a useful explanation of long run trends, but doesn’t provide a satisfactory explanation of the year-to-year volatility in inflation, even ex post.

Now let’s think about the sort of model that the average economist would recognize as an “explanation” for year-to-year variations in the inflation rate. When modeling inflation dynamics, many economists employ frameworks such as the Phillips Curve, the Taylor Principle, the Quantity Theory of Money, and the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Supply shocks may be added for greater realism, to explain the portion of inflation that is not attributable to excess spending.

All of these models have kernels of truth, and some major flaws.

Phillips Curve: Does a nice job of explaining why inflation fell in 1982 (as unemployment rose over 10%), but doesn’t tell us why inflation stayed low during the 3.5% unemployment of 2019, nor does it explain the high inflation of 1933-34, when unemployment was 25%.

Taylor Principle: Does a nice job of explaining why zero interest rates in late 2021 and early 2022 triggered high inflation, but doesn’t explain why inflation stayed so low during the 2010s.

Quantity Theory: Does a nice job of explaining why prices fell in 1921 and 1930, and why inflation accelerated during the 1960s and 1970s, but often fails to explain year-to-year fluctuations in inflation. (Different monetary aggregates give different results, but none of them are good enough to be policy guides.)

Fiscal Theory of the Price Level: Seems to explain some of the post-Covid inflation, but fails to explain why the reckless fiscal policy of 2015-2019 didn’t trigger high inflation, nor the inflation slowdown during the 1980s. Seems to work best for developing countries, whereas it did very poorly in Japan during the 1990s and 2000s.

All of these are what I view as engineering-type models of inflation. They try to model how certain “concrete steps” taken by policymakers led to bad results, at various points in history. But when these same formulas are applied to other points in history, they often don’t work. They tend to fail “out of sample”.

Because people are not used to thinking of macroeconomic aggregates such as inflation in finance terms, let’s start with a simpler example involving exchange rates, and then use the insights to examine inflation. Let’s compare the exchange rates for Taiwan and Hong Kong (both against the US dollar), over the past 40 years. Here’s Taiwan’s dollar:

BTW, that’s actually relatively stable, compared to many other currencies. But then there’s the Hong Kong dollar:

Since 1983, Hong Kong’s monetary authority has been targeting the exchange rate at 7.8 to the US dollar, (allowing slight fluctuations within the 7.75-7.85 range.)

How can we “explain” these two important macroeconomic variables? Hong Kong is easy to explain in one sense, and very difficult in another. The fixed exchange rate is definitely not a “price control”, at least in the sense that people use the term in microeconomics for price ceilings on gasoline or rent. This is an equilibrium market exchange rate, and there are no shortages or surpluses of Hong Kong dollars.

But of course the HK monetary authority is a monopoly producer of HK dollars, and they add or withdraw dollars as required to keep the exchange rate stable as the demand for HK dollars fluctuates over time.

Now here’s the key point. The HK monetary authority can stabilize the exchange rate at 7.8 to the US dollar, even if they have no ability to predict or even explain (ex post) the changes in the demand for HK dollars. They simply adjust the supply of HK dollars in such a way that the market is in equilibrium at the desired exchange rate.

Taiwan is far more difficult to model. Suppose you are an econ grad student at a Taiwanese university. Your advisor says, “Write a dissertation modeling changes in the Taiwan dollar exchange rate over the past 40 years.” Now you have your work cut out for you. Good luck!

There are a zillion things that might have affected the Taiwan exchange rate. You will narrow it down to “the usual suspects”, those variables commonly used by economists in other countries, and build a model. You will do some statistical work, i.e. search for “statistical significance”. Because you will probably be engaged in data mining, your results won’t actually be significant. The model won’t work out-of-sample, at least not well enough to be useful to either policymakers or investors.

To me, most of this sort of traditional macro is a waste of time. And my criticism even applies to much of the empirical work done by traditional monetarists, a group I am otherwise quite fond of. My vision of hell would be being forced to sit in a room and read dissertations like “Money Demand in Turkey.” It’s not so much that they are bad; it’s just that they are useless, at least at the margin. Perhaps a few early studies of money demand (Cagan, etc.) were useful in laying out the stylized facts—real money demand falls when the opportunity cost of holding cash rises, i.e., when interest rates and inflation rise. But now?

Money demand studies would only be useful to policymakers if it were wise to target the money supply. But it isn’t. Fiscal theory of the price level studies of inflation might be useful if it was wise to use fiscal policy to target inflation. But it isn’t. Phillips Curve models of inflation might be useful if it was wise to target unemployment. But it isn’t. Taylor Principle-type studies would be useful if it was wise to target interest rates. But it isn’t.

I don’t view inflation as being an important variable, and I certainly don’t favor targeting inflation. But most economists disagree. Because Tyler framed his critique in terms of inflation and not NGDP, I’ll respond by discussing how I’d think about modeling inflation, and then compare it to NGDP targeting at the end of the post. First I’ll explain how the Fed could target inflation, and then I’ll use that explanation to discuss what went wrong in 2021-22. Many economists will not recognize my “explanation” as an explanation, because it will be closer to finance than engineering.

Part 2: Target the forecast

Lars Svensson argued that central banks should “target the forecast”, which means they should set policy instruments at a position expected to achieve the desired outcome, the policy goal. Let’s make it simple and assume a 2% inflation target. In that case, the central bank should set policy such that their internal economic models predict 2% inflation. Svensson advocated using interest rates as the policy instrument. (This week the media is full of stories complaining that the Fed is not doing this—the Fed itself is predicting too much inflation.)

I also favor targeting the forecast, but differ from Svensson in a number of ways. He favors inflation targeting whereas I favor price level targeting (or better yet NGDP level targeting.) He favors using the interest rate as the policy instrument, I favor using the monetary base. He suggests using what I call an engineering-type forecasting model; I favor a finance-type model, or at least a hybrid model.

In this post I’ll compromise with traditional macroeconomists by considering a hybrid model, so that my proposal won’t seem quite so unorthodox. Indeed I’ll go even further, making the model 80% engineering and 20% finance. We know that the Fed actually does take finance considerations into account when setting policy (they discuss TIPS spreads, risk premia, etc.), so in this sense my proposal won’t be that far from actual practice. But in the end, there’ll be a few decisive differences, which will have important implications.

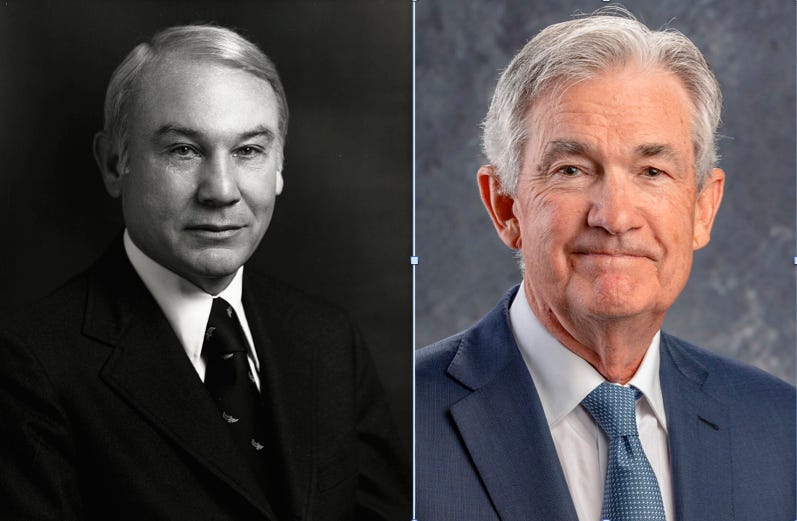

Here’s what Jay Powell could do. Create two divisions within the Fed, each with 50 economists. One division is instructed to come up with the best possible traditional engineering-style model for predicting inflation. I presume the Fed already has this sort of model.

The second division is instructed to come up with the best possible finance-type model for predicting inflation. This model would include variables such as TIPS spreads, but other variables would also be taken into account (such as estimates of risk premia, liquidity premia, etc.)

Unlike the engineering-type model, which is based on macro indicators that are released only monthly or quarterly, the finance-type model will give inflation forecasts that literally change minute by minute. The finance-type forecast will be a variable that changes in “real time”; it will look like an asset price, just as the Hong Kong exchange rate looks like an asset price.

From third grade, you may recall that the sum of an odd number and an even number is always odd. And the product of an odd number and an even number is always even. It’s not half even and half odd.

Similarly, a weighted average of a finance-type forecast and an engineering-type forecast is always a 100% finance-type forecast, at least in the sense that it moves around minute by minute in real time. That’s true even if an 80% weight is given to the engineering-type forecast and 20% to the finance-type forecast. (If I had my way, I’d reverse those percentages.)

Here’s the second key point: Fiat money central banks with infinite “ammunition” can always peg a nominal asset price. They can peg nominal exchange rates, they can peg nominal gold prices, and they can peg the price of nominal CPI futures contracts.

Jay Powell can then instruct the open market desk in New York to peg the hybrid forecast at 2% inflation. Here’s an imaginary conversation:

Powell: Use open market operations to peg the inflation forecast at 2%.

OM desk: But where do you want us to set the fed funds target?

Powell: There is no fed funds target, let the market set interest rates.

OM desk: (Increasingly nervous) Do you mean you want us to do money supply targeting?

Powell: No, let the market determine the money supply; just peg the inflation forecast.

OM Desk: But how?

Powell: Remember before 2008, when there was no IOR? You used open market operations to peg the fed funds rate. In the 1920s, you pegged the price of gold. I want you to use OMOs to peg the inflation forecast.

OM Desk: But before 2008 it wasn’t hard to peg the fed funds rate, because the market knew we were doing so. The rate would often move there before we even lifted a finger.

Powell: I plan to release the entire hybrid model to the press (and the financial community). They will engage in stabilizing speculation, just as they did in the old days.

OM Desk: But if they don’t?

Powell: If they don’t, and if you do as I’m telling you to do, then the skeptics in the financial community will lose money.

You can see that this approach takes some getting used to. Indeed even something like Singapore’s monetary policy, which targets exchange rates rather than interest rates, is a bit confusing to many people. To the average person, interest rates are monetary policy.

Part 3: If policy X targets Y, then bad policy X “explains” bad Y outcomes

Tyler wants me to present a useful model of inflation dynamics. Back in 2015, I published an entire book on inflation dynamics under the gold standard. It has extremely detailed models and is full of empirical data. It was ignored. But most people don’t care about the gold standard; so let’s think about inflation dynamics under a fiat money regime.

My model of inflation dynamics probably won’t even be recognized as a model by most people, but I’ll do my best to explain. Under a fiat money regime, the central bank basically chooses the trend rate of inflation. The central bank also makes mistakes. (They may also lie, but let’s keep it simple for the moment.)

Inflation dynamics consist of two parts:

Targeted inflation

Policy mistakes

Under a simple inflation targeting regime, all non-2% inflation is a mistake. In a more realistic flexible inflation targeting regime, temporary supply driven inflation shocks are OK, but inflation movements generated by demand shocks are considered a mistake.

I think you can see that under a simple inflation target, a model of inflation dynamics will essentially be a model of policy mistakes. Inflation will be 2%, plus or minus mistakes. Under a flexible inflation target, inflation will be 2%, plus or minus both policy mistakes and supply shocks. I have nothing of interest to add to the supply shock literature, so I’ll focus on policy mistakes. How do we model monetary policy mistakes, the undesirable part of inflation volatility?

This is a complex subject. At the simplest level, policy mistakes are a combination of not adhering to “best practices”, say not adhering to the 80%/20% hybrid model suggested in the previous section, plus failures that occur despite the use of best practices, perhaps due to a poor forecast from either the engineering-type macro model and/or the financial-type model.

What would it mean to willfully refuse to adhere to “best practices”? I’ll illustrate with an example. Imagine a hypothetical scenario where a former policymaker named Larry says, “Policy is too stimulative according to your own model, you are risking high inflation.” And a current policymaker named Jerome responds, “People are rioting in the streets, we need to create jobs.” In that case, the Fed does too much stimulus, even according to its own model of inflation.

But failures can also occur due to forecasting errors. We know that the world is complex, and models can never predict the effect of policy with precision. I view financial market forecasts as the least bad, but even they underestimated the upswing in inflation during 2021-22. And that failure cannot all be blamed on random supply shocks; even NGDP growth was far too high. So the proposal outlined in the previous section is not perfect.

But we are not done yet. It turns out that there are ways of greatly reducing the severity of mistakes. Some forms of inflation targeting are more naturally stabilizing than others. I was extremely pleased in 2020 when the Fed seemed to suggest that it planned to adopt something very close to one of the best techniques for stabilizing monetary policy—level targeting. Alas, it was a false dawn. The actual policy was far different from what was advertised. (In fairness, even economists within the Dallas Fed were fooled.)

In the next section I’ll argue that level targeting is by far the most effective way of stabilizing inflation (or NGDP). If I’m right, then not doing level targeting is the primary cause of inflation mistakes. That means that any model trying to explain inflation dynamics must begin with “not doing level targeting” as its primary focus.

As an analogy, if you thought that a stable exchange rate is the correct benchmark for optimal monetary policy, then any model of Taiwanese exchange rate dynamics needs to start with “not doing HK-style exchange rate pegging” as the primary explanation of the volatile path of Taiwan’s exchange rate. You’ll never figure out all of the complex factors that moved Taiwan’s dollar up and down over the past 40 years, but you can easily understand the importance of a central bank’s decision to float rather than fix the exchange rate.

Part 4: Level targeting leads to stabilizing speculation

For several decades, prominent macroeconomists like Michael Woodford have been emphasizing the value of “price level targeting”, which means returning to the pre-existing target path whenever there is a temporary price level overshoot or undershoot. This research grew out of insights in a 1998 Paul Krugman paper, which showed how the liquidity trap could be overcome if there were a credible policy promise to make up for near term inflation undershoots, with higher inflation after exiting the zero lower bound.

Ben Bernanke was also an advocate of this approach; at least he was before joining the Fed, where he discovered strong resistance to level targeting. He resumed his support for level targeting after he left the Fed. I recently wrote an entire paper on what I called the Princeton School of Monetary Policy, where level targeting plays a central role.

After the Global Financial Crisis and subsequent sluggish recovery, there was increasing acceptance of the insights of the Princeton School. In the 2020 policy review, the Fed adopted “flexible average inflation targeting” (FAIT), which was (or at least seemed at the time) pretty close to level targeting.

It turned out, however, that the Fed actual envisioned a FAIT policy that would make up for inflation undershoots with higher than 2% inflation in the future, but would not make up for inflation overshoots with below 2% inflation in the futures. In other words, it had nothing to do with targeting the “average inflation rate”; it was an asymmetrical make-up policy. And this asymmetry is the primary cause of the big inflation overshoot in 2021-22.

I don’t know of any economist that favors a strict 2% inflation target in an economy where there are supply shocks. All plausible inflation targets in the real world are “flexible”, and the 2020 FAIT initiative was no different. But flexibility wasn’t the problem in 2021. A flexible target is supposed to allow some inflation variation when there are supply shocks, but not allow demand shocks to affect inflation. At the time, James Bullard was president of the St Louis Fed, and he suggested that flexible average inflation targeting would be a lot like NGDP level targeting, allowing some variation in inflation due to supply shocks, but keeping nominal spending growth at a steady rate (perhaps 4%/year.) That was also my view.

The actual policy turned out to be nothing like NGDP level targeting, as (starting from late 2019) the path of NGDP overshot the 4% growth rate trend line by more than 11%. That was a huge policy mistake, an enormous amount of excess nominal spending. It’s a myth that the excess inflation over the past 5 years was mostly supply driven (except for a brief period of severe supply shocks.) Furthermore, very little of the overshoot can be attributed to bad forecasting; there was simply an unwillingness to do contractionary make-up policies.

Under true flexible average inflation targeting, or flexible price level targeting, or NGDP level targeting, the Fed would have been forced to adopt a far tighter monetary policy in the early 2020s. Due to supply shocks, inflation would have been somewhat above normal during certain months in 2021 and 2022, but the overall average rate of inflation over the past 5 years would have been close to 2%.

The FAIT policy turned out to be a sort of fig leaf to cover up an actual agenda of monetary stimulus to create jobs, the same sort of policy that failed when implemented in the 1960s. But the 1960s are a long time ago, and many people had begun to assume that inflation was dead for “structural reasons”, as if printing too much money no longer debases its value because of “trade”, or “demographics”, or “technology” or “weak unions” or some other nonsense. The last 5 years have been a brutal wake-up call for delusional MMTers—monetary policy still drives inflation.

If the Fed had actually done flexible price level targeting, or flexible average inflation targeting, or NGDP level targeting, there would have been stabilizing speculation in the financial markets during 2021-22. As an analogy, when the HK dollar moves close to the edge of the 7.75 to 7.85 band, market participants know that the monetary authority will eventually bring it back closer to 7.8. That creates stabilizing speculation.

In late 2021, if markets had known that the Fed would maintain an average inflation rate of 2%, then even if the Fed was temporarily “asleep at the wheel”, market interest rates would have shot up as the spending overshoot became obvious, and this would have preemptively tightened monetary policy even before the Fed acted with “concrete steps”. No central bank can ever maintain an effective policy regime with only concrete steps; you always need a credible regime of forward guidance. Nick Rowe once suggested that monetary policy is 1% concrete steps and 99% forward guidance, which means guidance about the central bank’s determination to take future concrete steps to hit its policy target.

Part 5: A model of inflation dynamics

In a moment, I’ll present my model of inflation dynamics. But it won’t look like a model. So let me first explain why traditional inflation models are not reliable.

Traditional models of inflation will include variables like “fiscal policy”. There will be some sort of “multiplier”, which supposedly predicts the impact of deficit spending on aggregate demand. But if a central bank is targeting inflation, it should always be trying to prevent fiscal shocks from creating undesirable movements in aggregate demand. Thus any undesirable movement in aggregate demand will be a monetary policy mistake. But rational central bankers should be equally likely to make positive and negative mistakes!

Suppose that Congress embarks on a reckless fiscal policy, as it did in the late 2010s. The Fed will see the deficit rise sharply, despite a strong economy. They will tighten monetary policy by an amount that they believe will keep aggregate demand growing at a steady pace consistent with 2% inflation.

Yes, monetary offset is not perfect. Central banks make mistakes. But there is no reason to expect mistakes to always be in one direction. A rational central bank would be equally likely to over-offset fiscal stimulus as it would be to under-offset fiscal stimulus. There’s no reason to expect fiscal policy to have any particular multiplier effect. (Apart from a small effect from changes in government output—but most discretionary fiscal policy is taxes and transfers, not government output.)

More importantly, even if a central bank makes occasional mistakes in responding to fiscal shocks, there is no reason to expect those mistakes to be consistently in one direction. Thus even if a certain fiscal action does have the anticipated impact in one particular case, it might have a completely different effect the next time it is employed. Any useful model of fiat money inflation dynamics is essentially a model of central bank mistakes.

So here is the framework for a model of inflation dynamics:

Long run trend inflation will be close to the central bank’s target, on average. With dovish central banks like the BoE, it may run a bit above target. For hawkish central banks like the ECB, it may run a bit below target. But the trend rate of inflation is essentially determined by the central bank. (This is under a fiat money regime; inflation averages close to zero under a gold standard.)

Central banks generally favor allowing some variation in inflation in order to accommodate supply shocks. While the shocks themselves are often unpleasant, the resulting inflation is actually desirable, relative to the alternative policy that would be requited to keep the overall price level perfectly stable. I have little to add to conventional models of supply side inflation, except to note that for some reason economists tend to overstate the importance of supply shocks. Even during the 1970s and 2020-24, almost all of the cumulative excess inflation was due to excess demand, to excessive NGDP growth.

Undesirable variation in inflation is almost entirely due to policy mistakes. Policy mistakes are more likely to occur under “let bygones be bygones” growth rate targeting, and are generally smaller under a level targeting regime. Policy mistakes also occur when the Fed puts too little weight on market forecasts, as was the case at its September 2008 meeting. Policy mistakes also occur when the Fed is embarrassed to change course because it would admit its previous policy decision was a mistake, as we saw in late 1937. Policy mistakes also occur when the central bank does interest rate targeting and underestimates the speed at which the natural interest rate can decline during a period of financial turmoil, as we saw in late 1929, and in 2008. There are an almost infinite number of reasons why monetary policymakers can make mistakes.

I understand why most economists would think this isn’t a model at all, and certainly not a satisfactory explanation of inflation dynamics. They want to see a set of equations. Just as I understand why most epistemologists don’t think Richard Rorty’s social theory of truth is real epistemology. They want clear rules for determining truth. In both cases, I think they are wrong. They want the impossible.

6. Is there any evidence that I am correct?

On several occasions, I’ve met really bright grad students who tell me they like my work, but need to keep a low profile until they get through their elite grad program. I’ve given up on influencing older economists, but hold out some hope that I might influence a handful of younger scholars.

So what do my supporters see that others do not? In my 15 years of blogging, I’ve gotten some things right and some things wrong. Overall, I think my track record is pretty good. But prediction is overrated; I suspect it’s my reasoning process that has gained me some followers. I’ve basically taken some off-the-shelf concepts that are widely accepted, and tried to show that mainstream economists were ignoring the clear implications of those concepts.

I’ll conclude this overlong post with one example of where I made a good call that utilized two mainstream theories, neither of which I invented:

The mainstream theory of inflation targeting suggests that central banks should offset fiscal shocks.

The EMH says that market forecasts are superior to other forecasts.

At the end of 2012, I pushed back against the Keynesian consensus that an imminent move toward fiscal austerity would significantly slow the economy, perhaps triggering a double dip recession. I pointed out that the Fed should offset the fiscal austerity, and I observed that the financial markets did not seem to be expecting a recession.

You could say I got lucky (as both real and nominal growth sped up), and I would not disagree. There might have been a recession. But I believe my more thoughtful readers were impressed by something else—they saw the logic of my argument. If the Fed policy regime suggests that it should try to offset fiscal austerity, and if the financial markets are not predicting a recession, then why should we expect a recession? Do you really trust “fiscal multiplier” models that much?

The Fed would generally like to avoid inflation volatility due to unstable aggregate demand. Therefore, it sets its policy instruments at a position expected to lead to fairly stable growth in AD. When it screws up, we get undesirable shifts in demand side inflation. Because the Fed is a large institution, its policy usually reflects the consensus of the economics profession. For that reason, the majority of economists almost always fail to predict important Fed policy errors. And because supply side events such as Covid and the Ukraine War are hard to anticipate, we also fail to predict supply side inflation. We are bad at predicting any sort of inflation volatility.

Right now, much of macro reminds me of astrology. Economists keep employing engineering-type models to predict things that cannot be predicted, such as business cycles and inflation variation. A model with 100 equations is not “rigorous”; the world is too complex to be modeled in that way. Macro needs to begin incorporating the insights of finance. Policymakers need to adopt a clear level target (preferably NGDP) and begin stabilizing asset prices closely linked to the target variable.

To convince me that I’m wrong you need to provide good arguments. In none of Tyler’s recent posts criticizing my approach to monetary economics has he ever said: “This macro outcome occurred in year X, and your model cannot explain it.” Just vague complaints of too much focus on “the nominal”. Sorry, the real problem is nominal.

I have a free book on the internet entitled Alternative Approaches to Monetary Policy. I encourage people to provide good arguments as to why this book is wrong. So far, they have not done so. I remain hopeful that I’ll get a critique that I can sink my teeth into.

The post is very clear, except it would have been good to explain upfront what distinguishes finance from engineering.

You think historically, so you think action-across-time matters. Samuelsonian Physics-envy economics has trouble with time—and especially the power of subjectivity (aka expectations) that action-across-time entails—because, oddly, time is not very important in most physics. A default of complete information, completely rational actors with no computational limitations is a default without action across time: it is more a frozen moment analysis. It is easy to turn into equations. (Rational Expectations was turned into a mechanism to use equations to get rid of the messiness of limited information expectations.)

You think of people as boundedly-rational people with limited information pursuing a range of strategies (with markets tending to winnow strategies), because that is what history reveals us to be. That is not easy to turn into equations. Hence, economics as a discipline has some tendency to ignore analyses that take history seriously but do not make for congenial equations.

Robert Fogel wrote an entire book explaining how the mass migration let loose by steamships and railways fractured the American Republic across its fault-line of slavery. He has been completely ignored because, like The Midas Touch, Without Consent or Contract was a work of analytical history even though, like The Midas Touch, it was steeped in economics. (As one might expect from a Nobel memorial Laureate.)

Fantastic post.

A pet peeve of mine is that the Fed acts as if forward guidance means saying a time frame for the position of an instrument (usually IOR but also QE/QT volumes). Then they continue obeying that promise well after it's clear that they need to adjust.