Nonzero

When land became capital

Where did the modern world come from? All sorts of answers have been provided to this question, including Christianity, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, the Protestant Reformation, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of capitalism, etc., etc. I doubt it will ever be possible to completely disentangle all of these factors, as material changes affected culture, and cultural changes affected the material world. Today, I’ll consider the role of land.

Economists traditionally speak of three factors of production: land, labor and capital. For economists, the term “land” refers to any productive resource freely provided by nature, including fishing grounds in the sea and minerals under the ground. Thus the tripartite factors can be views as human resources, non-human resources provided by nature (land) and non-human resources provided by humans (capital.)

Dutch liberalism

Throughout most of human history, farmland was the primary form of wealth. Although land could be improved, societies tended to advance toward something close to a steady state. Land could be purchased, or land could be stolen during warfare. But the total quantity of land was fairly stable.

Amazon.com describes Robert Wright’s book Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny as follows:

In Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny, Wright asserts that, ever since the primordial ooze, life has followed a basic pattern. Organisms and human societies alike have grown more complex by mastering the challenges of internal cooperation. Wright's narrative ranges from fossilized bacteria to vampire bats, from stone-age villages to the World Trade Organization, uncovering such surprises as the benefits of barbarian hordes and the useful stability of feudalism. Here is history endowed with moral significance–a way of looking at our biological and cultural evolution that suggests, refreshingly, that human morality has improved over time, and that our instinct to discover meaning may itself serve a higher purpose.

Under feudalism, the elites tended to disdain work and instead emphasized the martial virtues. Aristocrats studied the art of war, not business. One way of thinking about human progress is as a transition from viewing the economy as a zero-sum game to seeing it as a positive-sum game.

Many years ago, I read The Embarrassment of Riches by Simon Schama. I recall thinking that 17th century Holland was the first culture in history that was recognizable to me, that seemed at least slightly similar to the middle class culture I experienced growing up in Madison, Wisconsin. The way families were structured, the way children were treated, the way that affluent people usually worked, the residential streets lined with tall elm trees, even the focus on cleanliness. I was reminded of that book when I read the following passage in (of all things) a book on Wes Anderson:

The frenetic activity at this influential port [Amsterdam] opened up a span of unprecedented prosperity. A new merchant class appeared, having accumulated more personal wealth than had ever been known outside royal circles. The aristocracy, instead of seeking to marry their daughters off to noble families, suddenly favored the sons of merchants. Radical social changes soon followed.

Freedom of expression proliferated, including a revolutionary liberated press. A wave of new artists, including the likes of Rembrandt, broke with tradition and started painting portraits of everyday people. This span of time saw a rise in religious tolerance, scientific discoveries, medical breakthroughs, and an expansion of the rights of women in the Netherlands.

This era is often viewed as an important part of the development of modern capitalism. Deirdre McCloskey argues that capitalism is the wrong term to use, as ideas and innovation are the actual keys to the modern world, not the mere accumulation of capital. So let’s use the term liberalism to describe the innovations taking place in the Netherlands during the 16th and 17th centuries.

As an aside, I’m not suggesting that the Dutch invented liberalism, as you can find liberal ideas in places like Renaissance Italy and even ancient Greece. Rather I’d like to suggest that the Dutch played the single most important role in developing the framework for the modern world.

From landism to capitalism

If you insist on calling classical liberalism “capitalism”, then shouldn’t feudalism be called “landism”? And if Robert Wright is correct about non-zero-sum thinking being the key to human progress, then what are we to make of the fact that the Holland is best known for relying heavily on newly created land? To an economist, Holland is the only place where land isn’t “land”, it’s capital. A substantial portion of Dutch land is “non-human resources provided by humans”, i.e., capital. Is this fact somehow important to the development of liberalism? Did the reclamation of land instill a non-zero mindset?

I recently read Going Dutch: How England Plundered Holland’s Glory by Lisa Jardine, and came across the following quotation from a book by Vanessa Bezemer Sellers entitled Courtly Gardens in Holland 1600-1650:

The fight for land, the constant effort to keep it safe from the sea and foreign intruders, whether perceived as a real or an abstract threat, is one of the general themes and thoughts which have permeated not only Dutch culture in general but the art of Dutch gardening in particular. Land reclamation and cultivation and the creation of a peculiarly Dutch geometrical landscape interspersed with canals lay at the foundation of the art of gardening in Holland, so much so that the country itself became identified with a garden and its people with gardeners.

Note that prior to the development of railroads, canals were the most advanced form of transportation in Europe.

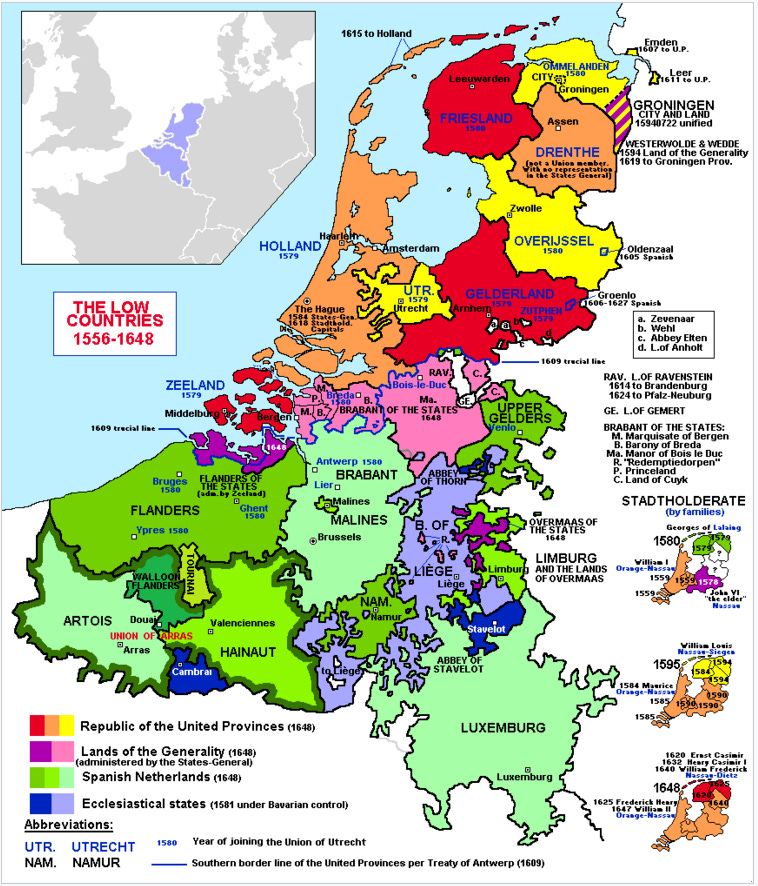

As an aside, some people object to the use of the term “Holland” for the Netherlands, as it is only one of the 7 provinces of the “United Provinces” during the 1600s (southern Netherlands is today’s Belgium).

When I visited the Netherlands in 1990, I traveled to seven different cities. Six of the seven were in Holland (the other was nearby Utrecht.) That’s because Holland contains the cities that played the greatest role in the Dutch Golden Age, the cities generally visited by tourists. You could say that Holland and Utrecht were roughly to the 7-member United Provinces what Dubai and Abu Dhabi are to the 7-member UAE—the most dynamic areas. (BTW, the UAE also reclaims land.)

I find it interesting that the one country that is famous for being partially built on reclaimed land is the same country that played a pivotal role in the development of modern liberalism, that is, the development of a culture with a non-zero-sum mentality.

Some will argue that Holland was not the first republic where commerce played a major role, and that Venice got there a century earlier. But isn’t Venice also built on reclaimed land? (And I doubt that Venice ever developed the sort of middle class that emerged in the Dutch Golden Age.)

Today, the Netherlands no longer leads the world in percentage of land that is reclaimed (about 17%). That honor now belongs to Singapore (25%). Interestingly, Singapore is now the number one nation in the Heritage index of economic freedom.

I suspect the Singapore neoliberalism/land reclamation correlation is spurious—in that case wealth led to land reclamation, not the other way around. But in the case of Holland, I wonder whether cultural changes arising from land reclamation had something to do with their economic success.

[I wish Putin had read this post before invading Ukraine. He would have learned that in the modern world, conquest is no longer the route to prosperity.]

From Holland to England to America

Lisa Jardine herself acknowledges that the relationship between England and Holland was more nuanced than suggested by her subtitle: How England Plundered Holland’s Glory, as influence moved in both directions during the 1600s. Nonetheless, this phrase does capture something important. English travelers were quite jealous of Holland’s success, and (especially after the Glorious Revolution” of 1688) Britain adopted many important features of 17th century Holland.

Jardine cites this report from the British Royal Society:

The Hollanders exceed us in Riches and Traffic: They receive all Projects, and all People, and have few or no Poor: We have kept them out and suppress’d them, for the sake of the Poor, whom we thereby do certainly make the poorer.

And this from a report to Cromwell during the Commonwealth period:

It is no wonder that these Dutchmen should thrive before us. Their statesmen are all merchants. They have travelled in foreign countries, they understand the course of trade, and they do everything to further its interests.

The Dutch and English East Asia companies came close to merging in 1650 and again in 1688, before deciding to remains separate. Nonetheless, Jardine reports that:

[C]ompetition between the two Companies ensured that the financial mechanisms developed by the Dutch quickly found their way into the English methods of dealing with import—export, customs and excise, taxation, record-keeping and accounting by emulation.

More recently, major Europe companies like Unilever and Shell began with the merger of British and Dutch companies.

Jardine reports that during the 1600s:

Downing worked tirelessly to reform English financial institutions so as to bring them in line with those he regarded as so supremely successful in the United Provinces. He did so in spite of the fact that England was a monarchy, while the United Provinces was a long-established republic, In doing so, he put in place the machinery for the ‘constitutional monarchy’ which would follow the arrival of William III in England in 1688.

Just as the Dutch invasion of England in 1688 succeeded with almost no bloodshed, the English grabbed New Amsterdam from the Dutch without firing a shot. Jardine quotes Charles II:

‘You will have heard of our taking of New Amsterdam,’ he wrote to his sister in Paris. ‘Tis a place of great importance to trade, and a very good town.’

Charles might be surprised by what happened over the next 350 years to this “very good town” of roughly 3000 souls—especially that wooden wall protecting the northern edge of the town.

The British were wise to allow the Dutch residents to remain in what was renamed New York. From today’s perspective, New York seems more “American” than the aristocratic slave-owning southern states or Puritan New England:

Although the Dutch language did not survive as the language of daily life in America, American English still carries traces of its Netherlandish ancestry—a ‘cookie’ is a koekje (small cake) and your ‘boss’ is your baas (master)—just as its culture still contains within it those foundational ideals and aspirations of tolerance, inclusiveness and fairness which had been the defining characteristics of the Dutch settlements in the New World.

From submerged land to Holland to Britain to America. Did the modern world begin with land reclamation?

PS. Of all the European countries that I have visited, the Netherlands seems the friendliest.

PPS. My grandmother’s maiden name was Clara van Winkle (no relation to Rip.) According to Wikipedia:

The village was first mentioned in 1289 as Winckele, and means "enclosed piece of land".

It’s in northern Holland.

"God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands"

America is the true intellectual descendent of the United Provinces. We were a British colony yes, but I'd argue that Britain was a Dutch colony, so.... by the transitive property....

And if Venice and Amsterdam prospered on land reclamation, surely.... New Amsterdam can as well: https://www.reddit.com/r/nyc/comments/2rkcjl/an_engineers_plan_for_a_greater_new_york/

Scott, my friends who are dutch are definitely nice people but they are also pretty blunt which can come across to other cultures as rude. Did you not experience this in your visit?