Discover more from The Pursuit of Happiness

School of Rembrandt, fake Vermeers, and AI art

What Turing tests tell us, and what they do not

[Happy Thanksgiving everyone. This post responds to Scott Alexander’s recent post on AI art, after a digression through the 1600s.]

In 1921, a survey identified 721 paintings done by Rembrandt. Since that time, the number of authenticated Rembrandts has decreased sharply:

The process of reducing the presumed oeuvre had begun already in early surveys. In his survey of 1921, Wilhelm Valentiner had considered the total number of paintings to be 711; in 1935 Abraham Bredius reduced that number to 630; in 1966 Kurt Bauch reduced it further to 562; and in 1968 Horst Gerson scaled it back to 420. . . .

In 1982, 1986, and 1989, respectively, three volumes of the projected five-volume publication A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings were published. The number of paintings being accepted as authentic works by Rembrandt was far smaller than what Gerson had presumed in 1968 (seen over the whole oeuvre as approximately 300 rather than 420), although the RRP team accepted some of the paintings Gerson had rejected.

Many of the rejected paintings were done by members of the School of Rembrandt, that is, by the many talented artists that studied under Rembrandt and copied his style. But if it is difficult to tell the difference between a painting by Rembrandt and one by his disciples, then in what sense can we say that Rembrandt was an exceptionally talented artist?

There are two factors that make Rembrandt special. First, Rembrandt invented the Rembrandt style of painting. As an analogy, if in 2025 someone writes a book on evolution that is more accurate than The Origin of the Species, no one would argue that this makes the author a better scientist than Charles Darwin. Many artists can produce a highly decorative painting done in the style of Monet or Renoir. But copycats would never be accepted as being on par with the originator of their styles.

More importantly, the inventor of a new style is generally at least slightly more talented than their students. The two skills (invention and artistry) are correlated.

The psychological depth of paintings like The Jewish Bride . . .

and The Return of the Prodigal Son . . .

. . . really does exceed that of Rembrandt’s disciples.

On the other hand, not all Rembrandts were at this level, and a lesser Rembrandt may be hard to differentiate from a painting by one of his more talented students, such as Carel Fabritius. The two paintings shown above are from Rembrandt’s late period, on which his reputation is based. This is also the period that produced his most profound self-portraits:

In the 1930s and 1940s, a very talented painter named Han van Meegeren successfully forged some Vermeers (and sold them to Nazis.) He chose to copy the early Vermeer’s less highly esteemed early style. Here is Vermeer’s very first painting:

And here’s Meegeren’s attempt to copy the style:

Today, the Meegerens looks inferior to even one of Vermeer’s weakest paintings, and far inferior to one of his late masterpieces:

And yet at the time, art experts were fooled by Meegeren’s forgeries. Today, even a mediocre art critic like me can easily spot the difference.

Scott Alexander recently asked his readers to guess whether various paintings were done by an AI or a human being. Most people had difficulty discriminating between the two. But as we’ve already seen, when this sort of “Turing test” is applied to many lesser works by the disciples of masters such as Rembrandt, even experts will occasionally be fooled.

This does not mean that I am unimpressed by AI art. Even if it falls a bit short of the very best work produced by the greatest artists, it’s sort of like Samuel Johnson’s comment about a dog walking on two feet—the fact that AI can produce even pretty good art is extraordinarily impressive. In addition, I am not arguing that AIs will never be able to invent new styles, or that they’ll never be able to push forward the frontiers of painting. I remain agnostic on the question of what sort of “super creativity” might eventually emerge.

Nonetheless, I’d like to tap the brakes a bit on enthusiasm over AI art. Here’s an AI image generated by Jack Galler that did not fool Alexander, but which he nonetheless described as “lovely”.

It’s a pretty picture, but perhaps a bit too perfect—too artificial looking. It certainly doesn’t take my breath away the way this portrait by Rubens does:

Even in famous art museums, 90% of the paintings are of only marginal interest. Outside of the Prado, true masterpieces are quite rare. In my view, AI has reached the stage where it is producing art similar to that lower 90%, which is itself a major achievement. But it’s the greatest stuff that makes the entire field worthwhile. A music analogy might be to compare Bach’s Goldberg Variations with the compositions of his talented children.

With the work of Rubens, Rembrandt, Vermeer and Velazquez, the art of painting reached a pinnacle in terms of what might be called “craftsmanship”, or skill with a paintbrush. After that, artists searched for new ideas. Painting became increasingly “conceptual”. I’d expect conceptual art to be easier for AIs to copy. Think of Warhol’s famous Campbell’s soup can, or an abstract work by Mondrian:

People who don’t closely follow the art of painting might assume that all art is about craftsmanship, and that my previous analogy to Darwin’s invention of the theory of evolution is off base. But when looking at modern conceptual art like this Mondrian, who can deny that invention of new styles plays an increasingly prominent role in artistic success. No ambitious young artist would ever say that she that wished to “paint in the Mondrian style.”

In a long post on complexity theory, Scott Aaronson makes the following observation:

[Y]ou might “know” a particular fact if asked about it one way, but not if asked in a different way! To illustrate this, Stalnaker uses an example that we can recognize immediately from the discussion of the P versus NP problem in Section 3.1. If I asked you whether 43 × 37 = 1591, you could probably answer easily (e.g., by using (40 + 3) (40 − 3) = 40 [squared] − 3 [squared] ). On the other hand, if I instead asked you what the prime factors of 1591 were, you probably couldn’t answer so easily.

“But the answers to the two questions have the same content, even on a very finegrained notion of content. Suppose that we fix the threshold of accessibility so that the information that 43 and 37 are the prime factors of 1591 is accessible in response to the second question, but not accessible in response to the first. Do you know what the prime factors of 1591 are or not? ... Our problem is that we are not just trying to say what an agent would know upon being asked certain questions; rather, we are trying to use the facts about an agent’s question answering capacities in order to get at what the agent knows, even if the questions are not asked. [126, p. 253]”

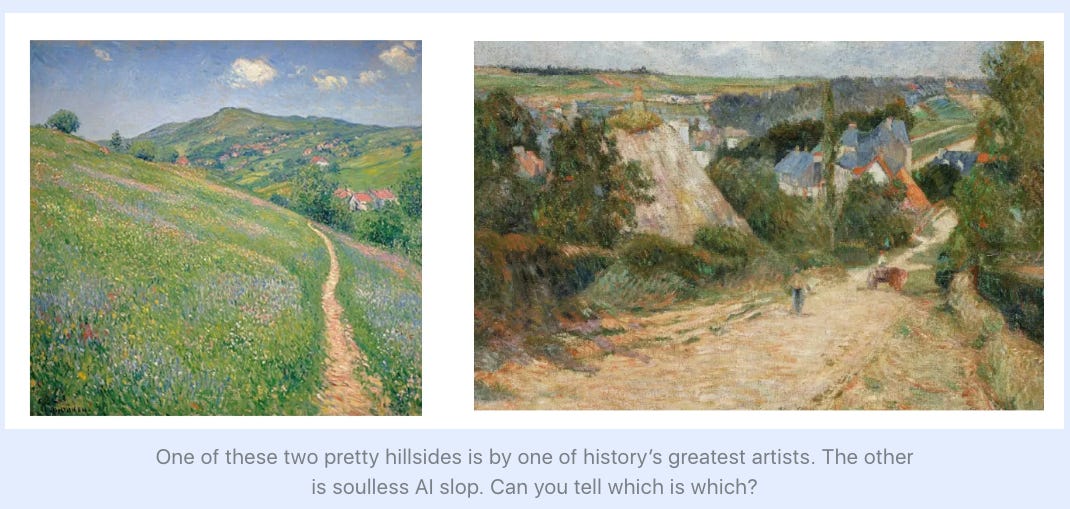

The reminds me of some of the art presented in Scott Alexander’s post:

If presented individually, I doubt whether I’d be able to tell whether these particular images were produced by an artist or a machine. But presented side by side, the one on the right (by Gauguin) looks more like something made by a flesh and blood human being, with a very particular vision for what he or she was trying to accomplish. Many people might find the one on the left to be prettier, but it’s also more like the sort of generic impressionist image you’d expect from a machine. It’s a visual cliché.

Alexander suggests that impressionism is the favorite style of his readers:

Most of the best-loved AI images were Impressionist; by chance, this category was somewhat AI-dominated in my dataset, so this could just reflect a love of Impressionist paintings (or a particular aptitude for AI in this area). But the human Impressionist painting I included (Entrance To The Village Of Osny, above) was actually quite unpopular.

Hmmm, I much prefer the Gauguin to the AI.

I have also found impressionism to be the favorite style of most people, at least among the more educated classes. (For all I know, Thomas Kinkade might be even more popular among the broader public.) When someone tells me that impressionism is their favorite style, I immediately suspect that they are not intensely interested in art. That’s not because there’s anything wrong with impressionism—it’s a perfectly fine style—rather because I think to my self, “What are the odds that they’d randomly pick impressionism from among all the other equally great styles, if they were not basing their taste on which style is the prettiest?”

If the preceding sounds elitist, keep in mind that I have exactly the same problem with music, poetry, dance, and lots of other art forms for which I do not have good taste—art where I cannot recognize what is best.

This also reminds me a bit of the P ≠ NP issue. I find it odd that I am pretty good at recognizing which paintings in a museum are good, even before getting close enough to see the name of the artist, while being appalling bad at actually producing art—probably worse than many third graders. I cannot solve the problem of producing good art, but can verify whether others have done so. Scott Aaronson makes some related comments:

The basic point can hardly be stressed enough: when complexity theorists talk about “intractable” problems, they generally mean mathematical problems that all our experience leads us to believe are at least as hard for humans as for computers. This suggests that, even if humans were not efficiently simulable by Turing machines, the “direction” in which they were hard to simulate would almost certainly be different from the directions usually considered in complexity theory. I see two (hypothetical) ways this could happen.

First, the tasks that humans were uniquely good at—like painting or writing poetry—could be incomparable with mathematical tasks like solving NP-complete problems, in the sense that neither was efficiently reducible to the other. This would mean, in particular, that there could be no polynomial-time algorithm even to recognize great art or poetry (since if such an algorithm existed, then the task of composing great art or poetry would be in NP). Within complexity theory, it’s known that there exist pairs of problems that are incomparable in this sense. As one plausible example, no one currently knows how to reduce the simulation of quantum computers to the solution of NP-complete problems or vice versa.

Second, humans could have the ability to solve interesting special cases of NP-complete problems faster than any Turing machine. So for example, even if computers were better than humans at factoring large numbers or at solving randomly-generated Sudoku puzzles, humans might still be better at search problems with “higher-level structure” or “semantics,” such as proving Fermat’s Last Theorem or (ironically) designing faster computer algorithms. Indeed, even in limited domains such as puzzle-solving, while computers can examine solutions millions of times faster, humans (for now) are vastly better at noticing global patterns or symmetries in the puzzle that make a solution either trivial or impossible. As an amusing example, consider the Pigeonhole Principle, which says that n + 1 pigeons can’t be placed into n holes, with at most one pigeon per hole. It’s not hard to construct a propositional Boolean formula ϕ that encodes the Pigeonhole Principle for some fixed value of n (say, 1000). However, if you then feed ϕ to current Boolean satisfiability algorithms, they’ll assiduously set to work trying out possibilities: “let’s see, if I put this pigeon here, and that one there ... darn, it still doesn’t work!”

The other two Scotts (with whom I shared a recent panel at Berkeley) are much smarter than I am, and I’m probably over my head even trying to discuss P and NP. But my intuition here is that an AI is immensely better than I am at producing reasonable paintings in the style of Rembrandt, but I’m somewhat better than an AI (for now) at verifying whether one Rembrandt painting is better than another. I presume that is telling us something important about the type of intelligence that each of us possess, but I’m not quite sure what.

To summarize, a Turing test of AI is telling us something interesting, but we need to be careful in interpreting the results. At the moment, AIs can produce reasonable versions of paintings done in the style of great artists. The more modern and “conceptual” the art style, the easier it is to fake. But they cannot yet invent interesting new styles (or can they?), and they cannot produce masterpieces in a traditional style like the baroque or impressionism, that is, a style that requires a high level of craftsmanship. As always with recent advances in AI, the glass is both half full and half empty.

One other point. If (as I suspect) the art of painting is now largely exhausted, then it might be unreasonable to expect either an AI or a human to produce an important new style.

PS. Instead of trying to produce a painting in the style of my favorite artists (Velazquez, Vermeer, Cézanne), perhaps I should try to fake a Mondrian.

PPS. The highest price ever achieved for an AI-produced work of art is $1,084,800, for a portrait of . . . Alan Turing.

The most interesting (to me) aspect of Alexander's post is that 5/11,000 people scored 49/50 (98%).

That could happen randomly if all people had 82% skill, which was clearly not the case.

It could also happen if a dozen people had 98% skill, except then someone would almost certainly would have gotten a perfect score by chance.

The most likely answer is that 100-200 people had >90% skill, and everyone else had lesser skill, or simply rushed so they could see the answers

I suspect the challenge would have been easier without human-operated computer-generated graphic art mixed in; most of the pictures had tells, but you had to be familiar with the genre.

The Riverside Cafe (extra chair legs) and Anime Girl in Black (excessively detailed armpits) were two of the most obvious AI examples. In the case of the Gauguin, the road leads to the village. In the AI version, there is a narrow footpath to nowhere and a random smattering of isolated houses.

Art isn't just about rendering something, it is about leading the eye on an emotional journey by drawing the eye toward significant details or symbols, however abstract.

Thomas Hoving once had a statement to the effect that it's hard to identify a forgery done in your own era, but much easier to identify one done decades ago. The principle could well apply to some of the comparisons in this post.