Systemic analysis

Looking beyond the headlines

Driving home today I heard a few news stories that discussed various outrages. I suspect that many NPR listeners would focus on the superficial nature of the problems and not look for the deeper causes.

The tragic fire in Hong Kong:

At least 150 people died in an apartment fire in Hong Kong. I don’t know the exact cause of the fire, but I do know certain facts about Hong Kong

a. Hong Kong has one of the most well-functioning economies on Earth.

b. There is one glaring exception to the previous point: Hong Kong’s housing system is extremely dysfunctional.

c. Hong Kong has one of the most laissez-faire economic systems in the world. For instance, their outstanding (and profitable) subway system is privately owned.

d. There is one glaring exception to the previous point: Hong Kong’s housing system is mostly government run.

Trump’s pardon of a major Honduran drug dealer.

Trump’s opposition to violent crime seems pretty sincere. Recall how he responded to the famous Central Park rape case back in 1989. Trump was so angered by this event that he refused to accept the fact that the five accused suspects were later exonerated. Recently, he has used the military to go after suspected drug runners in the Caribbean. The suspects are being executed without a trial. All this is consistent with Trump’s hostility toward criminals.

[BTW, the outrage over the execution of those two guys clinging to the wreckage seems almost beside the point. I agree that it was awful, but it’s no different from the ones killed in the first strike. If you agree that the war on drugs should be extended to international waters, the appropriate response is to arrest the suspects. I get that killing people clinging to wreckage seems more pathetic than killing suspects standing calming on the deck, but in both cases you have decided to execute criminal suspects, rather than have them arrested and tried in a court of law. These were not soldiers killed in battle, as the “war of drugs” is just a metaphor, like the “war on cancer.” It’s not a “war crime” because we are not at war. It’s just a garden variety crime. Naturally, Trump insists these guys are guilty, just as he insisted the Central Park 5 were guilty.]

So how should we think about Trump’s recent pardon of one of the world’s biggest drug dealers? Is it out of character? Not at all. Trump is strongly opposed to crimes committed by ordinary people, but views heads of state quite differently. Contrast those Central Park rape suspects with someone like Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who ordered the killing of an American reporter. Or consider Vladimir Putin, who has committed numerous war crimes in Ukraine. Trump clearly respects those two leaders, despite their many crimes. Trump pardoned Former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández because he considers national leaders to be above the law.

My own view is that national leaders should not be above the law. But I’ve seen quite respected pundits argue the opposite, that “lawfare” should not be used against heads of state. That seems to be the view of the Supreme Court, at least for crimes committed while carrying out public policy. If you think this sort of double standard is appropriate, then the pardon makes sense.

What if North Korea were the world’s richest country?

North Korea is obviously an economic basket case. But what if it were not? What if it were richer than the US or Switzerland or Norway? What then? I suppose that neoliberals like me could argue that, “It’s just one data point, communism is still a really bad economic system.” But even I would find that argument to be a bit implausible. Could communism really be all that bad if the world’s most strictly communist system were the world’s richest country? (I don’t wish to get sidetracked with a debate over whether North Korea is actually the world’s most communist place; feel free to substitute some place like Cuba—it won’t change my argument.)

What’s the point of this nonsensical counterfactual thought experiment? Almost no one suggests that a hardcore communist system is likely to result in world-leading wealth creation. But I’ve seen a number of intellectuals claim that democracy doesn’t work very well because “voters are stupid”. In that case, wouldn’t it be equally embarrassing if the world’s most democratic country, the place that had more than 50% of all national referenda during the 20th century, the place where income tax increases must be approved by ordinary voters, turned out to be the best governed place on Earth?

As in my imaginary North Korea thought experiment, you could just say that it was just one observation. Nonetheless, it would certainly seem to be an embarrassing fact for democracy skeptics.

Switzerland just had a referendum on whether to institute a wealth tax on estates above 50 million SF. That’s a threshold that probably applies to less than one percent of the Swiss population. The proposal was rejected by 79% of Swiss voters. This referendum occurred two weeks after I posted this claim:

I doubt whether anti-capitalist populists would do well in Switzerland or Singapore.

A small news story in Orange County

A very short news story in the OC Register caught my eye:

Four people were found dead in a Fullerton home Tuesday, Oct. 21, possibly the result of overdoses, police said.

Officers responded . . . after a caller said four of his friends had overdosed and weren’t breathing, according to Fullerton police. . . .

Detectives who were conducting an investigation into the deaths don’t believe there’s any threat to the public.

No further details were available, including when the victims died or what drug or other substance may have led to the deaths.

Most people would view that story as a piece of evidence in favor of banning drugs. I suspect that it is more likely to end up being a piece of evidence that drugs should be legal. To be clear, I don’t not know exactly what happened in this particular case and can only speculate. And even if I am correct, it certainly would not prove that drugs should be legal, it would merely provide one piece of evidence.

If one person were found dead, I might wonder if it was a suicide. With four deaths, I suspect that the victims accidentally ingested far more of a dangerous drug than they anticipated. For instance, I’ve read numerous stories of ordinary people dying because they didn’t know the cocaine they snorted was laced with fentanyl. I would not be at all surprised if something like that happened here.

To be clear, narcotics are risky even if you know exactly what dose you are receiving. But drugs become vastly more dangerous in the underground markets, where there is no reliable way to be certain as to the dose that one receives. This explains a large proportion of drug deaths.

With legalization, that sort of accidental overdose would become much less common. On the other hand, legalization would boost demand for drugs, and thus the total number of overdose deaths might increase even if the danger from any given drug use declined.

In this post, I’m not really trying to argue for drug legalization, rather I’m trying to argue that a systematic analysis of the drug problem, an analysis that looks beyond the headlines, leads to a stronger case for legalization than the average person would assume by looking at headlines about overdose deaths.

If you favor legalization, don’t be intimidated by snide comments like “Oh, so you want CVS to sell cocaine and heroin?” Consider the following facts:

During 1880-1910, America allowed cocaine and heroin to be sold by retailers. During that period, the public was aware that these drugs were dangerous. Some people became addicted, and that’s why they were eventually banned. But it was not obvious that a ban was appropriate, which is why it took so long.

During 1880-1910 alcohol probably caused much more harm that other narcotics. It was banned almost a decade after narcotics, but the ban was lifted in 1933. Today, alcohol is legal and sold by retailers.

When people mock the “absurd” idea of allowing retailers to sell drugs, recall that for long periods of American history this was perfectly legal, despite the fact that the public knew these drugs were dangerous and causing people to become addicted. Also recall the fact that during this period alcohol caused even more harm than narcotics. And recall the fact that alcohol was briefly banned, and that this did indeed reduce alcoholism. And recall that despite the fact that the alcohol prohibition did reduce alcoholism, the ban was eventually lifted. And recall the fact that the case for banning alcohol is in many ways far stronger than the case for banning narcotics, because in a black market economy accidental overdoses of alcohol are far less common than accidental overdoses of narcotics.

Again, I’m not trying to argue that all drugs should be legal. That might be the best policy, but it also might be best to legalize cocaine and Oxycontin and continue banning heroin and fentanyl. Perhaps that intermediate regime could be defended on a “harm reduction” basis. I don’t know. Rather I’m suggesting that most discussion of this issue is quite superficial and ignores all sorts of relevant considerations. It’s not enough to say “Duh, drugs are obviously bad.” Yeah, I know that. The drug war is also obviously bad. Fentanyl deaths skyrocketed when we started restricting Oxycontin prescriptions.

To me, the story of the four deaths in Fullerton (a college town), which got very little press coverage, is a far bigger deal than the Epstein files, with far great implications for public policy. Four deaths is very sad.

What sort of taxes do voters actually hate?

Brian Albrecht has an excellent post on public choice issues surrounding taxes. But I’m going to slightly quibble about one specific claim:

Another area of disagreement is taxation. Economists tend to prefer taxes like property taxes; voters despise them. Economists think corporate taxes are among the worst ways to raise revenue; voters think corporations should pay more. Economists generally prefer consumption taxes to income taxes, whereas voters tend to prefer income taxes.

That might be true, but as you probably know I’m very suspicious of public opinion polls. Instead, I like to think in terms of revealed preference. And while we do not have a clean test of this hypothesis, there is a fair bit of circumstantial evidence that voters hate income taxes more than they hate property taxes.

In numerous previous posts I’ve pointed to the clear evidence that voters are moving to areas with no state income tax, even when they have fairly high property tax rates (as in Texas.) Again and again we see faster population growth in zero income tax states than in nearby states with a positive income tax (Washington vs. Oregon, Tennessee vs. Kentucky, South Dakota vs. Nebraska, Texas vs. all its neighbors. We have also seen a recent movement toward lower state income tax rates, as other states try to reverse a loss of residents. Here is AI Overview:

States Cutting Income Taxes in 2025

The following states reduced their individual income tax rates effective January 1, 2025, continuing a multi-year trend of tax reform across the country:

Indiana: Reduced its flat tax rate from 3.05% to 3.00%.

Iowa: Transitioned to a single flat tax rate of 3.8% from a top rate of 5.7%.

Louisiana: Adopted a flat tax rate of 3%, down from a top rate of 4.25%.

Mississippi: Reduced its flat tax rate to 4.4% (with plans for further reductions).

Missouri: Trimmed its top rate to 4.7% from 4.8%, as part of a phased plan to reach 4.5%.

Nebraska: Lowered its top rate to 5.2% from 5.84%, with a goal of reaching 3.99% by 2027.

New Mexico: Restructured its tax brackets to reduce rates for low- and middle-income taxpayers, while keeping the top rate at 5.9%.

North Carolina: Cut its flat rate to 4.25% from 4.5%, with a future reduction to 3.99% planned for 2026.

West Virginia: Reduced its top marginal rate to 4.82% from 5.12%.

South Carolina: Made a temporary income tax reduction permanent, with further cuts possible in the future.

States with 2024 Tax Cuts

Several other states also implemented income tax cuts earlier in 2024:

Arkansas: The top individual income tax rate dropped to 3.9% from 4.4%.

Georgia: Continued its transition to a flat tax, reducing the rate to 5.39%.

Kentucky: Took another step toward eliminating its income tax, reducing the rate to 4.0%.

Montana: Cut its top marginal rate to 5.9%.

Actual existing nationalism

I’ve frequently argued that nationalism and communism are the two great evils of the 20th century. I highly recommend a recent article by Alex Nowrasteh & Ilya Somin, which makes some similar arguments:

Nationalism’s failures in the 20th century, from starting two world wars to genocide to jingoistic economic policies that have immiserated millions, rank it as a horrific failed ideology, second only to communism. Conservatives, classical liberals, and libertarians rightly mock leftists who claim that “real communism hasn’t been tried” or that “the Soviet Union wasn’t really communist” when confronted with the disastrous effects of their policies. Those who make similar excuses for nationalism are on no firmer ground.

High trust societies achieve better outcomes

In The Great Danes, I argued that places with high levels of civic trust achieve better economic outcomes. Robin Brooks points out that Denmark has a very low level of public debt, despite having a high level of government spending:

In today’s post, I look at how foreign ownership of government debt has evolved from 2019 (before the COVID debt splurge) to now. I do this for 40 advanced and emerging market (EM) countries. Denmark has the biggest rise in foreign ownership, consistent with the idea that markets are gravitating towards low-debt safe havens (Denmark’s government debt is 30 percent of GDP).

America’s government spends far less than the Danish government as a share of GDP. And yet, the US now pays nearly 4.1% interest on 10-year Treasury bonds, whereas the Danes pay only 2.6% interest.

Our heavy interest burden partly reflects the dysfunctional nature of our political system. It should be easy to run large budget surpluses with US levels of federal spending (roughly 23% of GDP.) If we eventually resort to inflation as a way to finance the debt, it will not be because other solutions are infeasible, it will be because the grown-ups have all left the room.

People have begun speculating on what Kevin Hassett would do to interest rates. That’s the wrong question. It’s not clear that the Fed chair determines Fed policy, and even if he does the relevant policy is NGDP growth, not interest rates. The actual question of interest is what sort of inflation/NGDP growth does the Fed intend to generate? Once that question is answered, the market sets the interest rate. Banana republics choose inflation, while responsible countries try to pay their bills. So far, I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the roughly 2% PCE inflation rates embedded in current TIPS spreads. Investors seem to be betting that American voters don’t like inflation, and will eventually pressure Congress to shape up. I hope the market is right.

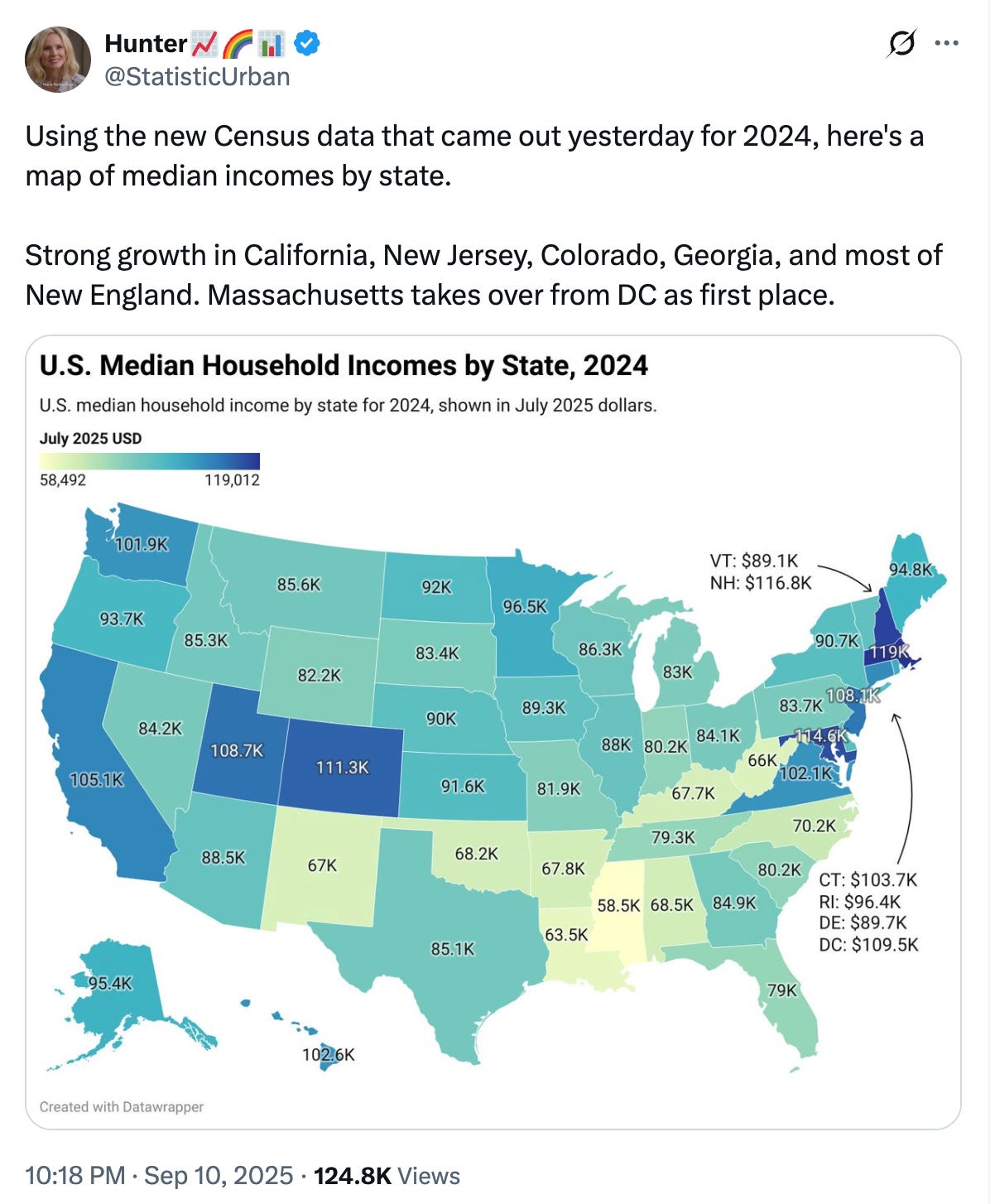

Speaking of civic virtue, Utah is the only red state with a median household income above $100,000. Although Trump won Utah fairly easily, he considerably underperformed the typical GOP presidential candidate. It seems that Utah conservatives are a bit more concerned than other Republicans about issues such as corruption and hostility to immigrants.

Here’s AI overview:

Utah: Has the highest percentage of its population identifying as having Danish descent.

Look closely, and you’ll see that everything’s connected. . . .

PS. New Yorkers might want to stop looking down their noses at Mormons, as Utah is now 20% richer than New York:

Who’s to blame?

Systemic analysis is all about looking beyond the surface. Most people respond to a bad experience in a business by blaming the business. I do that on some occasions, but more often I blame government regulation. Today, I had a bad experience at CVS. I blame the government regulation that prevents me from buying medication without a prescription. In my view, bad regulations and a bad tort law system explain more than 90% of my bad experiences with the private sector. The other 10% are customer service phone lines.

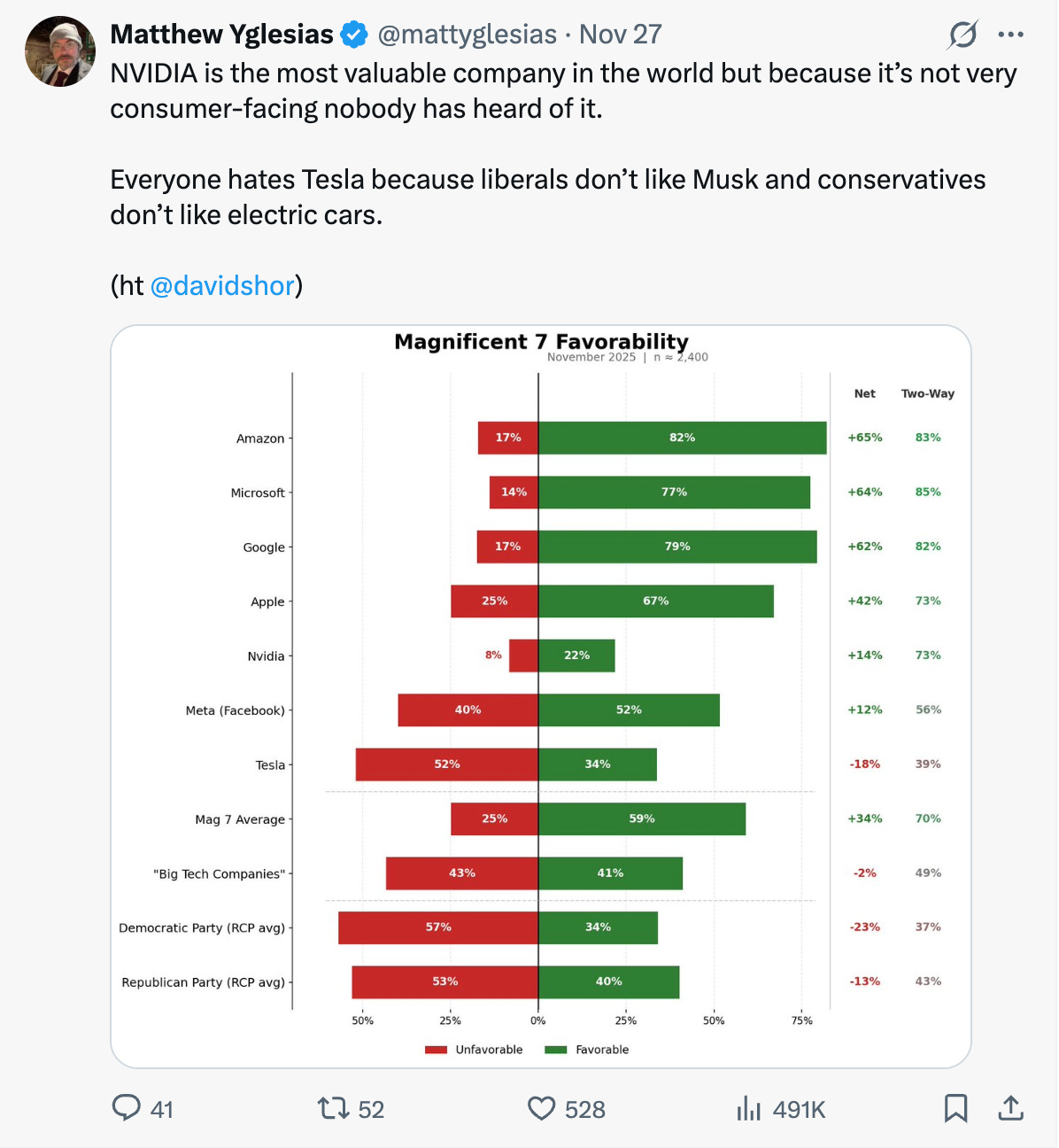

People like specific things more than general things:

The public hates big tech companies, big government and property developers, but they like specific big tech companies, specific government programs and their local homebuilder.

Why does advocacy seem to always end up being counterproductive?

Environmentalists often oppose solar, wind, hydro and nuclear. Anti-trust advocates often oppose low prices. Immigration advocates often (unintentionally) create a public backlash against immigration. Affordable housing advocates tend to make housing less affordable. Labor advocates enact policies that lower real wages and raise unemployment. Safety advocates make the world less safe by making the perfect the enemy of the good. Civil rights advocates enact discriminatory policies. Peace advocates often give aid and comfort to aggressors. Medical ethics advocates enact policies that kill tens of thousands of people. Education reformers usually make kids dumber.

If it were just one or two examples you could write it off as an anomaly. But this sort of outcome seems closer to the norm. Perhaps every advocacy movement starts out with one or two good ideas. But once they become established, they just keep going. They move right past the point of optimal advocacy, to a position where their efforts are counterproductive. They just cannot leave well enough alone.

I’m a fan of the Chinese Doom Scroll Substack where the author translates a selection of posts from Weibo. Great set on nannies today. But also this on the Hong Kong fire:

“Heard a Hong Kong architect talk about the skyscraper fire recently and he mentioned a shocking bit of logic.

Why were these skyscrapers getting their outer wall renovated at the same time? Why do all 8 buildings need scaffolds builded? Why have the scaffolds been there for over a year?

The reason is actually because no Hong Kong construction company has that many workers to work on all those buildings at once. You need thousands of people working at the same time for that, and once the work is done, those workers will have nothing to do and nowhere to go. So normally, you would build scaffolds on the buildings one by one and work on them one by one.

But in that case, it’ll be really hard for the construction company to get the money from the homeowners up front all at once, and it’ll be a slow process getting the rest of the funds, and there’s no guarantee you’ll get all of it. The construction company wrapped all the buildings up so they can get the downpayment all at the same time, but they can still only work on one building at a time. This way, the scaffolds stay on the buildings for a very long time. Over a year, in this case.

It’s because these buildings stayed wrapped up for so long that the bamboo dried out. Once a fire broke out, the risks is really high that it’ll spread to other buildings. Normally, the gap between the buildings was enough to prevent fires, but the extra width of the bamboo scaffolds made the gap smaller, causing this multi-building fire. So the biggest reason for this accident is bad construction order policy. They shouldn’t have wrapped all the buildings up for so long, just so they can get more of the downpayment.

I don’t know whether or not this Hong Kong architect was right, but if it’s true, then this is a very important lesson to learn. There should be laws made that if skyscrapers are getting worked on at the same time, the safe distance between them needs to be recalculated to avoid multiple construction projects going on in high density areas to prevent a similar situation.”

Comments say, “I don’t know if it’s possible to make a law that skyscrapers are not allowed to be taller than how high the escape ladders can reach or how high the fire hydrants can pump.”

“The last building to get renovated is so sad. It has to be all wrapped up for several years.”

“Hong Kong people are so polite. If it was me, due to my health reasons, I wouldn’t be able to put up with it for more than a month before I got frustrated.

"Hong Kong has one of the most laissez-faire economic systems in the world. For instance, their outstanding (and profitable) subway system is privately owned."

Which was also true, at one time, of NYC's subway. The one August Belmont (property developer and race horse breeding financier) built in 1904. But when he wanted to build a second line the politicians, greedy to share in the revenues, refused to let him do it without cutting them in on the deal. That was the seed of New York City's destruction of the subways (where it is today).