Discover more from The Pursuit of Happiness

Why does almost everyone assume that interest rate targeting is best? Let’s start with the wrong answer: “Because they are stupid.” When an overwhelming majority of experts all line up behind one policy, we need to take their views very seriously, even if we hold an alternative view. In the end, I’ll argue against interest rate targeting, but first I would like to understand why there is an interest rate monoculture in the field of monetary economics.

If you asked economists why they favor interest rate targeting, most would probably respond by bashing money supply targeting, as if that’s the relevant alternative. And if you asked them why money targeting is bad, they’d typically respond in one of two ways:

1. Velocity is unstable.

2. The 1980-82 failed monetarist experiment showed that money supply targeting doesn’t work.

Neither is a good argument. Conventional economists are probably right about money supply targeting not being optimal, but not for the reasons that are generally cited. We need to understand the flaw in the conventional critique of monetarism, before we can move past the stale monetarist/Keynesian debate.

Let’s first start with velocity. It’s true that velocity is unstable. But so is the natural rate of interest. It’s true that a stable money supply growth rate might produce bad results due to velocity instability. But it’s equally (indeed even more) true that a stable interest rate might produce bad results due to natural interest rate instability. Indeed the latter policy is likely to produce an even more explosive disaster.

The Fed pegged interest rates at a constant level from 1945 to 1951, and that policy caused major problems. In 1949, the economy plunged into deflation, and unemployment rose to nearly 8%. By the spring of 1951, inflation rose to over 9%. A stable interest rate policy is a highly unstable monetary policy. Neither a fixed money supply rule nor a fixed interest rate rule makes much sense, for similar reasons.

Unstable velocity is not an argument against money supply targeting; it’s an argument that the money supply growth target should be frequently adjusted to offset changes in velocity, just as the interest rate target is now adjusted to offset changes in the natural interest rate.

Second, the 1980-82 money supply targeting program was not a failed monetarist experiment. It was a flawed monetarist experiment. In fact, it worked far better than the failed Keynesian interest rate targeting experiment of 1965-80. That policy consistently failed to control inflation; indeed it got worse and worse as time went by. The so-called failed monetarist experiment brought inflation under control relatively quickly.

But didn’t the monetarist experiment result in high unemployment during 1982? Yes, it did. But even using Keynesian policy tools a successful anti-inflation program will produce several years of very high unemployment. That’s the Phillips Curve problem.

It’s truly bizarre to run a policy regime for 15 years, utterly fail to control inflation, switch to an alternative policy regime, quickly control inflation, and then declare that the second regime failed and we need to go back to the first regime. How does that make any sense?

Then how did we end up in such a weird position? Several reasons:

1. Because Milton Friedman was so persuasive, money supply targeting began to be equated with “stable money growth rule”, a completely different concept. When this specific version of money supply targeting seemed to become sub-optimal in 1982, the entire concept seemed discredited.

2. Monetarists wrongly thought that policy affected NGDP with a long and variable lag. For this reason, they were often reluctant to promote a discretionary money targeting regime that attempted to offset velocity changes.

3. Most people, even most economists, find interest rate targeting more intuitive. They can see how an interest rate cut would make next door neighbor Fred more likely to buy a car. They can’t see how swapping $1 billion in bank reserves for $1 billion in T-bills would make Fred more likely to buy a new car.

4. Real world central banks prefer to use interest rate targeting.

Now that I’ve convinced you that money supply targeting was unfairly rejected, I’d like to reject money supply targeting. Yes, you can do open market operations to move M2 to a position where markets expect 4% NGDP growth, but why not cut out the middleman and just do open market operations until markets expect 4% NGDP growth?

That can be done in two ways. The radical approach is my NGDP futures market “guardrails” regime. The less radical approach is to have the Fed look at a wide range of macro data and asset market data, and frequently update its estimate of expected NGDP growth. Then, do as Lars Svensson suggests and target the forecast.

None of this requires any sort of interest rate targeting. You can get rid of IOR and go back to using open market operations as the primary policy tool. Then target a composite market NGDP estimate in the same sort of way that central banks in Singapore or Hong Kong target the exchange rate and let the market decide the interest rate.

Both money supply and interest rate targeting share one flaw in common. They both add needless complexity to the monetary policy process, making mistakes more likely. Policy will be most stable if you have a 4% NGDP target, level targeting, and always set the monetary base at a position where the market expects on target NGDP growth. Use open market operations (OMOs) to control NGDP expectations and let the market decide the interest rate.

John Cochrane has an excellent (and long) post that explains his views on monetary policy. He rejects both the monetarist approach and the Keynesian view of how interest rate targeting works. Here he comments on monetarism:

But the bigger problem is that this theory just doesn’t apply to today’s world. The Fed does not control money supply. The Fed sets interest rates. There are no reserve requirements, so “inside money” like checking accounts can expand arbitrarily for a given supply of bank reserves and cash. Banks can create money at will. The Fed still controls the (immense) monetary base (reserves+ cash). The ECB goes further and allows banks to borrow whatever they want against collateral at the fixed rate. The Fed lets banks arbitrarily exchange cash for interest-paying reserves. Most “money” now pays interest, so raising interest rates doesn’t make money more expensive to hold.

Monetarist theory is perfectly clear: The Fed must control the money supply. If it does not do so, and either targets interest rates or provides “an elastic currency” meeting demand, the theory does not work. “Money” and “bonds” must be distinct assets. If money pays the same interest as bonds, or if bonds can be used as money, the theory does not work.

It’s a nice theory. It might be a theory of how the Fed could control inflation, or perhaps how money supply (by the Fed, gold discoveries, etc.) did control inflation in the past, even as recently as the 1980s. It might even be a theory of how the Fed should control inflation. (I’m throwing bones to my many monetarist friends.) But it is not a theory of how the Fed (and the ECB, BOJ, EOE, etc.) does control inflation by raising interest rates without any money supply control.

I mostly agree with these comments, with two exceptions. First, I don’t see the current system as a “problem” with monetarism; it’s a problem with the current system. Of course it is true that we don’t have money supply targeting in “today’s world”, but that’s no argument against money supply targeting.

I also slightly disagree with the final sentence. After money supply targeting ended in 1982, the Fed continued to use open market operations to control the fed funds rate. I would describe the 1982-2008 policy as follows:

The open market desk is instructed to move the monetary base to a position that moves the fed funds rate to a position that the FOMC believes best achieves its dual mandate.

It is misleading to suggest that this doesn’t involve any “money supply control”, as if money were unimportant. Yes, you can make that claim for the post-2008 IOR era, but not the 1982-2008 era. Back in 2008, the monetary base was 98% currency, which wasn’t even close to being a substitute for bonds. In a supply and demand sense, base money was more like paper gold, a very unusual asset with a distinct demand (mostly hoarders seeking anonymity).

Even if open market purchases initially injected reserves, the fact that banks didn’t want excess reserves meant that it almost all went out into currency, and quickly. It is 98% accurate to say the Fed was controlling the price level by adjusting the stock of currency to meet the changing demand of hoarders in places like Mexico, Venezuela and Russia. Interest rates were merely an indicator of whether more or less currency was needed to hit their macro targets.

We could go back to the pre-2008 regime, but instruct the open market desk to stabilize NGDP expectations, not fed funds rates. That’s my preference.

Later on, John quotes me (and another skeptic of modern macro):

Scott bemoans

I was asked to name the most important paper published in my field (which is macroeconomics) over the past ten years. I couldn’t think of any.

And replies:

They are right, I think, about the state of affairs, but they are wrong about its implications. There is a consensus theory of monetary policy, that has utterly dominated academic work since about 1990 — the “new Keynesian” model. The basic framework hasn’t changed much. Academic work has extended that framework with many additional complications. But there are now clearly gaping holes in its foundations, elephants in the room about its failure to describe facts, and a deep divergence between its predictions and the Standard Doctrine.

That is the most exciting time for a field! The existing paradigm is crumbling. The policy world follows a consensus doctrine with no respectable economic foundations. Basic issues are up for grabs: Do higher interest rates lower inflation? How? When? With what preconditions (like, fiscal policy)? Is an interest rate peg possible? How much of inflation is under the Fed’s control anyway? What frictions underlie monetary policy? Do we need money, credit, financial frictions to get off the ground? This is physics 1904. This is a moment in which very simple basic thinking and basic matching theories to facts has the potential to revolutionize our understanding. This should be a great time to be a young macroeconomist!

I agree that it is a gaping hole in the model when we live in a world where central banks use interest rates targeting and we don’t even know which direction interest rates impact inflation. (And as you know, I think it’s nonsensical to ever reason from a price change.)

I’d say “This is physics 1904” only if the leading physicists back then could not even agree on whether gravity attracts or repels objects. Yes, it’s that bad. It reminds me more of 50 years of arguing over Copenhagen vs. Many Worlds. I’m not optimistic about either the reality of quantum mechanics or the reality of the monetary transmission mechanism being resolved in my lifetime, but perhaps Cochrane is right that brilliant young economists have a juicy target to shoot for.

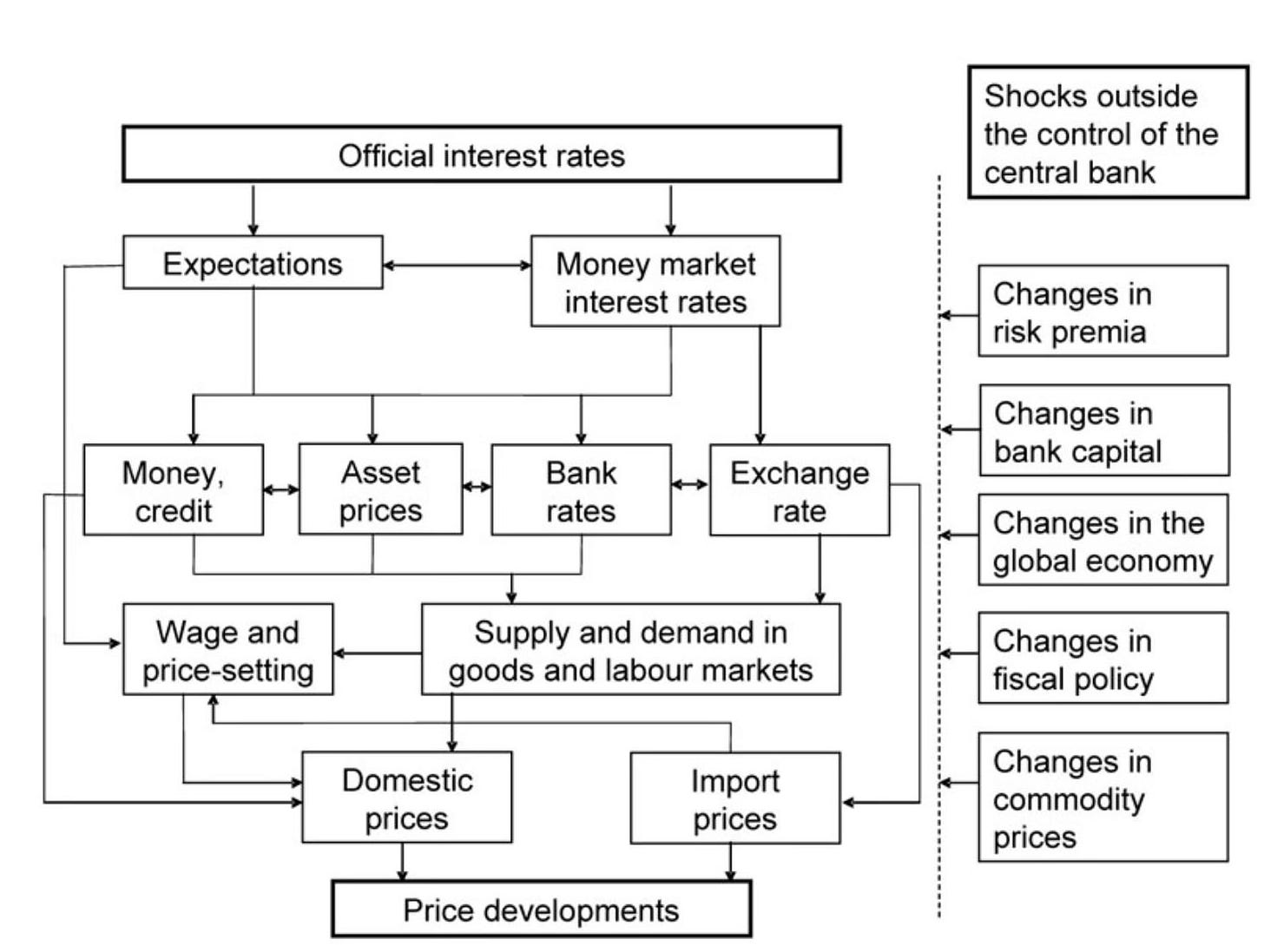

In John’s final two paragraphs we swing between claims that I’m wildly supportive of to something I’m strongly skeptical about. He discusses how the major central banks claim to fix “market dysfunction”, and then shows an ECB graph of the “monetary transmission mechanism”:

And then comments:

Apparently they really think they have scientifically valid understanding of this Rube-Goldberg contraption, together with the technocratic capacity to direct all the arrows, should they become “dysfunctional.”

If only I had John’s talent for writing.

But in the final paragraph I think he takes a wrong turn:

A last thought: Throughout all of macroeconomics, the economic damage of recessions comes entirely because prices are sticky. If prices were flexible, monetary policy would result in costless inflation, instantly, and no unemployment. Economists and central bankers take “stickiness” as given and go on to advocate complex policies that take advantage of them. But if sticky prices are the key economic problem causing all the pain of recessions, why does essentially nobody advocate policies to unstick prices? Instead we have intervention after intervention to make prices more sticky: price controls, rent controls, union support, and so on. Similarly, if bond markets are routinely “dysfunctional,” should we not figure out why and fix them, rather than use this as an excuse for central banks to go on a shopping spree?

The “essentially nobody” remark obviously doesn’t apply to specific policies like rent control, which almost all economists oppose. He seems to be suggesting that a broader deregulation of prices can prevent nominal shocks from having real effects.

America had a fairly laissez-faire economy in 1920. Nominal wages fell substantially during 1920-21. And yet unemployment rose sharply, as prices fell even faster. Yes, government deregulation would help somewhat (the recovery from the 1921 slump was rapid), but we need to accept the reality of sticky wages and nominal debt contracts, and establish a monetary policy that can be optimal in the world we live in.

PS. Over at Econlog, I just published a related post.

Prof. Sumner,

Has anyone tried to encourage the people behind Polymarket to create a giant, highly-liquid NGDP futures market? If not, are there any likelier potential candidates out there? Couldn't Tyler Cowen, Alex Tabarrok, Yglesias, or Noah Smith get someone's attention in order to do that?

I thought, but pls correct me, that the gist of Cochrane’s argument is that money supply is endogenous. In other words, it is just that money supply is not controlled by the central bank under the current regime, but it cannot be controlled under the current technology.