The problem of underconfidence

Central bankers as reluctant superheroes

I don’t keep up with the superhero genre, so I asked ChatGPT to find some examples of underconfidence:

After Peter Parker is bitten by a radioactive spider, he gains superhuman abilities—but at first, he doesn't fully understand or control them.

Other characters with a similar arc include:

Clark Kent (Superman) in some origin stories (like Smallville), where he gradually learns to control his immense strength.

Eleven from Stranger Things, though not a traditional superhero, also fits the theme of discovering and misjudging her powers at first.

I suspect that if you searched every published book, magazine and pamphlet ever written, you’d find vastly more discussion of the problem of overconfidence than the problem of underconfidence. Indeed, when I type the word ‘underconfidence’, my Substack editor underlines it as if it is misspelled.

Central banking is a rare case where underconfidence is the main problem. To be clear, I am not suggesting that it is the only problem—I suspect the mistakes of 2021 mostly reflected overconfidence that inflation would remain low. Rather, I’ll argue that most of the biggest monetary policy mistakes throughout history have been caused by underconfident central bankers. Indeed, next to dating, central banking may be the area where underconfidence does the greatest harm.

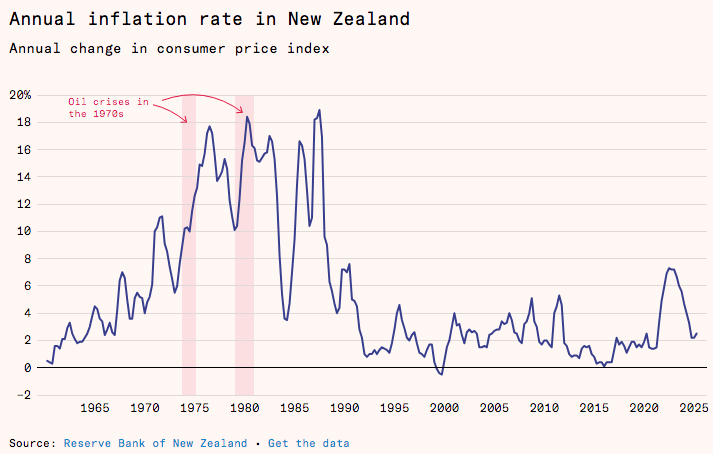

Over at Works in Progress, Oscar Sykes has produced an excellent essay on the history of inflation targeting. If I were to do a TLDR for his essay, it would be that inflation targeting wasn’t adopted until the 1990s because policymakers were underconfident of their ability to control inflation. In February 1990, the Bank of New Zealand adopted a 0% - 2% inflation target. Sykes’s article shows a New Zealand cartoon depicting pigs flying with the central bank’s inflation forecast written on the belly. Very funny. But look at what happened next:

Of course, the Kiwi success could be easily dismissed, as New Zealand is merely “a small country that is far away”. But just a year later, Canada also adopted an inflation target:

These were unveiled in February 1991 through a joint announcement between the government and Bank of Canada. The plan established time-based targets to reduce inflation from 6.2 percent to between 1 and 3 percent by 1995. In March 1991, Canada’s Crow met with fellow central bankers in Basel at the Bank for International Settlements. His shift to inflation targeting faced significant criticism. Former Deputy Governor John Murray characterized the prevailing sentiment: ‘Why would any prudent central bank risk its reputation by accepting such an uncertain and explicit mandate? The chances of [meeting the targets] were regarded as extremely small and would likely undermine the Bank’s credibility’.

Why were central bankers so skeptical? It turns out that central bankers have a long history of underestimating their power.

For 30 years after the Great Depression, the consensus view of policymakers was that the slump had been caused by financial stability problems, not tight money. That all changed when Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz published A Monetary History of the United States. They showed that poor monetary policy played a crucial role in the Great Contraction of 1929-33. Later research somewhat modified their claims by focusing on problems with the international gold standard. But even that research blamed central banks in places like the US and France for hoarding excessive stocks of monetary gold.

By the late 1960s, the gold standard was no longer a constraint on monetary policymakers. And yet most economists continued to blame non-monetary factors for the big inflation of 1966-81. Only much later did economists realize that excessive monetary expansion was the cause of the Great Inflation. Ben Bernanke is a good example of a mainstream economist that now views Fed errors as being a major cause of both the Great Depression and the Great Inflation. And in his memoir, Bernanke admitted that the Fed erred in not easing monetary policy at the first meeting after Lehman failed.

This is all part of a longstanding tradition in macroeconomics, where the consensus almost never identifies major policy mistakes in real time, precisely because policymakers generally follow consensus opinion. The profession has no desire to blame itself.

At a FOMC meeting from late 1937, one participant warned that if the Fed corrected a previous policy mistake (the two reserve requirement increases of early 1937), the public might begin to assume that they had caused the recession that was just getting underway:

“We all know how it developed. There was a feeling last spring that things were going pretty fast … we had about six months of incipient boom conditions with rapid rise of prices, price and wage spirals and forward buying and you will recall that last spring there were dangers of a run-away situation which would bring the recovery prematurely to a close. We all felt, as a result of that, that some recession was desirable … We have had continued ease of money all through the depression. We have never had a recovery like that. It follows from that that we can’t count upon a policy of monetary ease as a major corrective. … In response to an inquiry by Mr. Davis as to how the increase in reserve requirements has been in the picture, Mr. Williams stated that it was not the cause but rather the occasion for the change. … It is a coincidence in time. … If action is taken now it will be rationalized that, in the event of recovery, the action was what was needed and the System was the cause of the downturn. It makes a bad record and confused thinking. I am convinced that the thing is primarily non-monetary and I would like to see it through on that ground. There is no good reason now for a major depression and that being the case there is a good chance of a non-monetary program working out and I would rather not muddy the record with action that might be misinterpreted. (FOMC Meeting, November 29, 1937. Transcript of notes taken on the statement by Mr. Williams.)”

A near textbook example of bad epistemics and bad ethics.

Most of the Fed’s major policy mistakes occurred because the Fed was insufficiently aware of the fact that monetary policy drives nominal aggregates such as inflation and NGDP. It is unfortunate that the term ‘monetarism’ became associated with the preference for money supply targeting. What we really need is a term for people who believe that movements in nominal aggregates are essentially a monetary phenomenon (reflecting shifts in both money supply and money demand.) Moneyism?

In a recent post, I argued that a tight money policy by the Fed caused the Great Recession. This is because I believe that a plausible counterfactual policy of NGDP level targeting would have prevented a deep recession from occurring in 2008-09. So why hasn’t the Fed adopted my ideas? I suspect it is due to a mixture of underestimating the potency of monetary policy—the ability of central banks to offset financial and real shocks—and worry that a rigorous level target would make it more obvious that the Fed is to blame for any demand side recession (or high inflation).

[I would hate being Superman—imagine being blamed by grieving mothers after failing to prevent some sort of disaster.]

At some point in the future, all of this will become clear. Central bankers will no longer be able to dodge responsibility for nominal shocks. At some point we will have such a large array of futures markets linked to important nominal aggregates that it will become clear that monetary policy drives the nominal economy. Like a reluctant superhero, central bankers will be dragged kicking and screaming into accepting responsibility for a power that they already have, a power they achieved when the gold standard ended.

I don’t believe that academic research will trigger this policy revolution. (In my own case, my blogging has been far more influential than my published research.) Once again, here’s Oscar Sykes:

Inflation targeting didn’t emerge from academic research. [New Zealand Finance Minister] Roger Douglas wanted to show his commitment to price stability, and inflation targeting offered a way to do it. While economists were crucial in translating this political initiative into a workable institutional framework, it was Douglas who put the idea on the table. After New Zealand and Canada demonstrated inflation targeting’s effectiveness, other countries quickly followed suit. Delivering the results is what caused consensus to shift.

Read the whole thing.

Dr Manhattan might be a good metaphor. Profound reluctance to act and self-imposed limitations. Also he’s the only true superhero, all the others are nothing compared to him.

Bernanke advised the BoJ to adopt nominal price-level targeting. But when he became Fed chairman he kept the 2% inflation target which he always missed on the downside. It was not symmetrical. Had he taken his own medicine (NPLT), the economy would have performed better.