This is part one of a two part series. The second post will be entitled “What economists don’t know.” (I can already hear the snide remarks: ”Will that post be much longer?” It is.)

Economists are out of favor in Washington, Brussels, and Beijing. Throughout history, that’s generally a sign that bad policymaking is on the way. So every once an a while it is useful to remind people that economists actually do know some useful things. I will use a recent article in The Economist to illustrate how economics makes some useful and non-obvious claims about the world, beyond the well known cases like comparative advantage. To be clear, these points will be obvious to most of my readers. But trust me, they aren’t obvious to most people, even to most highly intelligent people.

When I talk to “normal people”, I’m often struck by the fact that they don’t seem to regard economic policy as offering much of an explanation for the relative wealth and poverty of nations. I suspect that is partly because they are often not even aware of many of the most highly destructive policies, and if they were they would not understand why economists view them as so destructive.

Here’s David Henderson:

[Gunnar] Myrdal stated, “Rent control has in certain Western countries constituted, maybe, the worst example of poor planning by governments lacking courage and vision.” His fellow Swedish economist (and socialist) Assar Lindbeck asserted, “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing.”

Most people would be utterly bewildered by a comparison between bombing and rent control. And yet even left-wing economists like Myrdal hold quite negative views of the policy. Economists really do know a few non-obvious things.

The Economist has an article on economic policy in Nigeria, which by the end of the century may become the world’s second most populous country (after India.) The TLDR is that despite being rich in oil, Nigeria is a poor country partly because of abysmal economic policymaking. (It’s not a long article; read the whole thing.)

Suppose you said the following to the average person: “Nigeria is a poor country where people have trouble affording basic necessities like gasoline. Therefore the government provides subsidies to keep the price down, and also has regulations to prevent price gouging.”

I’ll bet you could find tens of millions of American who would nod their heads, and go on with their lives. Here’s how the average economist would react:

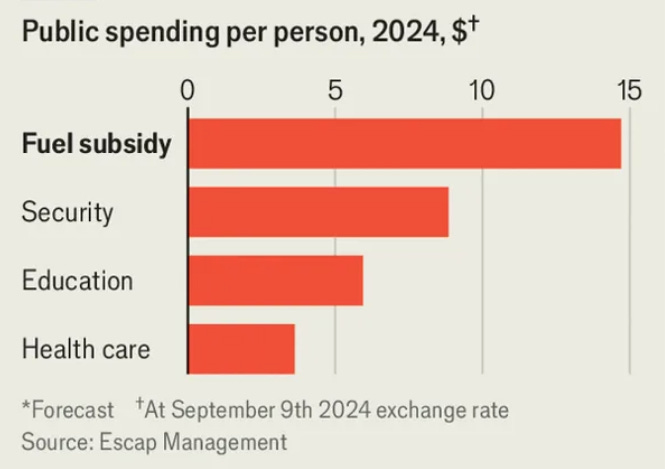

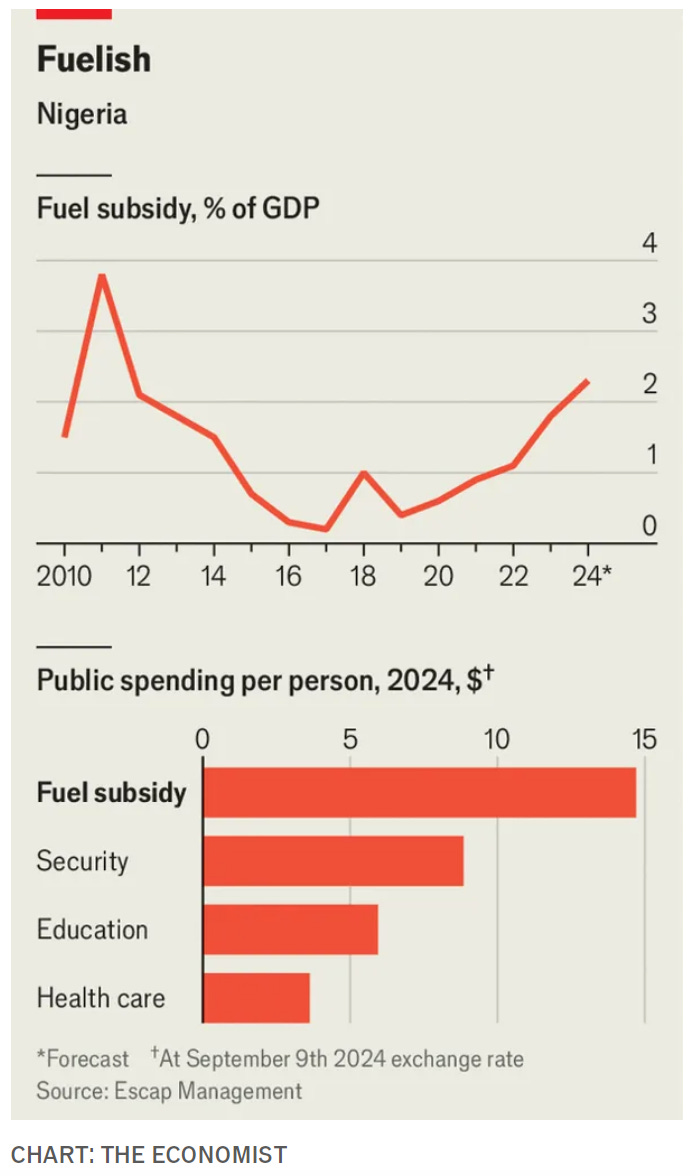

Where to begin. Let’s start with the odd fact that they have both subsidies and price controls. Why aren’t subsidies enough? Won’t they hold the price down? Unfortunately, the Nigerian government doesn’t have enough money to subsidize all Nigerian gasoline sales, and thus relies of price controls to restrain prices in the remainder of the market. The following data illustrates the problem:

The average person is bored by statistics. In contrast, economists often see vast human tragedies in a few dry statistics. Fuel subsidies are the largest government program in Nigeria, dwarfing the combined expenditure on education and health care. Not only can the Nigerian government not afford to subsidize all gasoline sales (despite being oil rich), even its limited program starves resources from far more valuable endeavors. The Economist has one of the best one sentence explanations I’ve encountered of why poor countries are poor:

This policy is typical of a state which is simultaneously too big, in that it asserts control of countless things best left alone, and too small, in that it fails to supply basic services.

OK, the program is expensive and inefficient, but surely it has some benefits. Let’s not forget about the equity/efficiency trade-off. Maybe it helps poor Nigerians to buy gasoline. Unfortunately, even this excuse doesn’t work. Nigeria is not like the United States; the vast majority of people there don’t even own cars. The fuel subsidy overwhelmingly favors the more affluent classes in Nigeria.

But even if the policy had had some modest redistributive effects, it would almost certainly have been counterproductive because of its grotesque inefficiency. When it comes to living standards for the average person, growth is an order of magnitude more important than distribution. (Another thing economists know that lots of average people do not.)

As you’d expect, the price controls created all sort of black markets within Nigeria, as well as external smuggling:

The system is corrupt and leaky: much of the cheap petrol is snaffled and smuggled abroad, though how much no one knows. . . .

Because the petrol subsidy is so costly, the government cannot afford it, and subsidised petrol often runs out. For days the streets of Lagos have been snarled, as huge queues of cars form outside petrol stations. “I’ve been waiting 16 hours,” grumbled one frustrated motorist. Not far away, black-market traders holding jerry cans and plastic tubes were offering to fill tanks for three times the official price.

The current government tried to reform the system, but had to backtrack. Economists have developed a range of public choice theories that help us to understand the persistence of such obviously counterproductive policies:

Yet reform faces steep obstacles. The opacity of the current system makes it easier to loot, so insiders will strive to preserve it. . . .

More importantly, Nigerians have long planned their lives around cheap fuel, so scrapping the subsidy would be both painful and unpopular. Many Nigerians see subsidised petrol as the only concrete benefit they receive from their government, rather than as a drain on revenues that could usefully be spent on other things. . . .

The government’s weak mandate and fear of provoking riots may tempt it to keep at least part of the subsidy. Moreover, because so many politicians squander public funds, they are unpersuasive messengers for painful changes. “It is difficult to tell people to be patient and to convince investors that Nigeria is prepared for reforms when the presidency is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on another jet,” laments Esili Eigbe of Escap.

This highlights the role of civic trust. In The Great Danes, I showed that by some measures Denmark was the most neoliberal society on Earth. It is also the country with the highest level of civic trust. America is closer to Denmark than Nigeria, but we shouldn’t pat ourselves on the back. The Swedish government was sufficiently trusted to enact a congestion pricing scheme in Stockholm. Political polarization in America led New York to drop a similar proposal at the last moment.

Economists also have a better sense of the data. Recall the scene in Crazy Rich Asians where the billionaire’s son is asked if he is rich, and replies ”We’re comfortable”. I suspect that most of the people who want the SALT deduction restored to the tax code see themselves as “average Americans”. They aren’t. While they are certainly not all wealthy, the deduction did heavily favor people in the top 10%. And in a country where about half the population has gone to college, and the biggest debts are accumulated by students at private colleges or grad programs, student loan relief is not an egalitarian policy.

Economists are much more aware than average people of the damage done by a wide range of economic policies, including bans on direct sales of autos by manufacturers, rent controls, occupational licensing laws, the Jones Act, prohibition of kidney sales, sugar import quotas, nationalized air traffic control, residential zoning and a zillion other examples I could cite. Check out twitter to see all the highly intelligent people who were shocked a few weeks back to discover that our ports have third world levels of efficiency. Like, you didn’t know?!?!?!

I’ll bet not one pet owner in a hundred knows that they pay too much for vet services partly because my niece was not able to fulfill her lifelong dream of becoming a veterinarian due to corrupt and inefficient government regulations. These problems exist throughout out economy. Everywhere. Go to Nigeria, and you’ll see the same sort of problems multiplied tenfold.

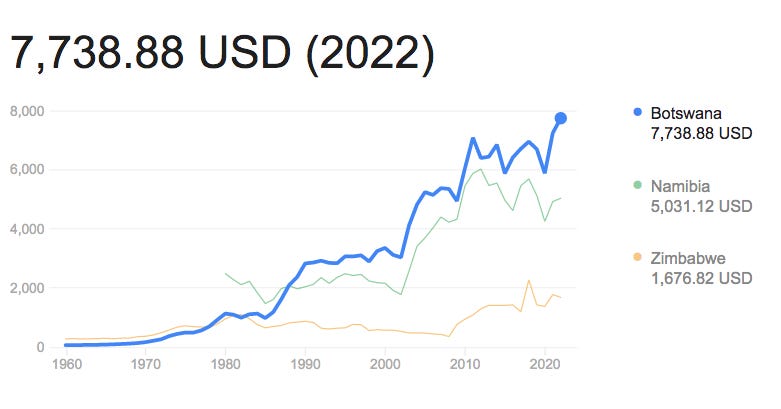

I’m not suggesting that all problems are due to bad economic policies. Obviously, Africa has much lower levels of human capital than the US. But even within Africa you can see many side-by-side examples of the important role of policy—most notably in the Zimbabwe-Botswana comparison:

Yes, Nigerian immigrants to America tend to be from the educated classes. But even so, these immigrants are far more productive under our policy regime than they would have been back in Nigeria.

To be sure, the libertarian prescription of less government is not always best. Economists have all sort of arguments for a government role in areas like monopoly, externalities, public goods, national defense, redistribution, etc. In my view, a better argument is that simple rules are often best. “Don’t subsidize gasoline” is a simple rule. “Don’t have price controls on gasoline” is a simple rule. Unlike Nigeria, almost all successful countries follow those simple rules (although the US did have gas price controls during the 1970s.)

And even where the government does play a constructive role, a simpler approach is usually better. Cash grants are better than food stamps, and food stamps are better than government farms. Cash is better than rent vouchers, and rent vouchers are better than public housing projects. Tradable pollution permits are better than command and control regulation of utilities.

In my next post discussing what economists don’t know, I’ll argue that we as a profession overestimate our ability to understand complex problems, and we overstate our ability to do complex policymaking.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of complex problems, and hence a lot that economists don’t know. Even worse, they don’t seem to know how much they don’t know.

I love love LOVE this post, particularly this: "Cash grants are better than food stamps, and food stamps are better than government farms. Cash is better than rent vouchers, and rent vouchers are better than public housing projects. Tradable pollution permits are better than command and control regulation of utilities."

Excellent post!! Another simple rule that I like, "End All Tax Preferences" so the tax code is simple.