From the beginning of the modern era, intellectuals have been engaged in the endless search for a prescription to shape economies in such a way as to achieve progressive goals. When these proposals involve a government takeover of the economy, they are called socialism or communism. When the proposal calls for government intervention to reshape and redirect a basically market economy, it’s called industrial policy. Here I’ll argue that industrial policies rarely succeed, as their architects underestimate the complexity of the problem. (The basic critique is Austrian/Chicago School, but I’ll try to offer some novel arguments.)

Some countries are successful. Some countries are unsuccessful. All countries do at least some industrial policy—even Hong Kong (in housing). From these three facts, we can deduce that:

All successful countries do industrial policy.

All unsuccessful countries do industrial policy.

These points may seem obvious, but are often overlooked by proponents of industrial policies. I’ll start by refuting the very weak case for what might be called “vulgar mercantilism”. In part 2, I’ll address some of the more respectable arguments for industrial policy that are made by highly qualified economists. Only in part 2 do we get to “what economists don’t know”. Most good economists know everything I’ll say in part 1.

Part 1: 1 + (-1) = 0, not 2

Every so often a non-economist will publish an article refuting the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage. The form of this argument is always pretty much the same: “Economists may think that free trade is best, but they don’t understand that the real world has blah, blah, blah.” Actually, economists do understand blah, blah, blah, and they also understand that these considerations have no bearing on Ricardo’s theory of trade. Sorry, but it’s actually kind of insulting when these amateur economists act as if foreign trade experts like Doug Irwin have never heard their simplistic arguments.

A second technique of the mercantilists is to find some examples of industrial policies done in successful economies, and then argue that these economies are successful because of those policies. Given that all economies do industrial policies, the mere existence of a set of industrial policies cannot by itself explain the success of that economy. That’s not to say we cannot learn anything—a close look at their experience may provide a wealth of information. I’m merely pointing to what should be obvious; one cannot assume that any given economic success story is explained a specific policy that the country happens to utilize, without a much more careful analysis.

The easiest way of making this point is to first go back in time to the 1960s, and recall the very active debate between proponents of the “import substitution model”, which emphasized building up domestic industry behind a tariff wall, and the “export-led growth model”, which emphasized development through policies encouraging openness to international trade. The import substitution people championed the approach used in Latin America, whereas the export-led growth people pointed to East Asia. At the time, Latin America was considerably richer than East Asia.

Obviously, East Asia won the competition, as its economies have vastly out performed those of Latin America. And to be fair to the other side, I’m not even entirely sure that the gap can be fully explained by their policy choices—maybe culture also played a role.

While there was disagreement as to which model was best, there was pretty general agreement that Latin America was focusing on import substitution while East Asia was focusing on export led growth. But once East Asia won the battle, import substitution proponents switched their argument. “Actually (they argued), East Asia did well because of industrial policies such as tariffs and export subsidies.”

Obviously, this sleazy debating tactic looks bad for proponents of mercantilism. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they are wrong. Instead, there are many other reasons to reject this new argument for mercantilism:

Many of the advocates focus on South Korea, which is certainly a highly successful development story. But apart from communist countries (PRC, Vietnam, North Korea), all of the culturally “Confucian” economies of East Asia have been highly successful. If South Korea’s success were due to mercantilist polices, how can we explain the success of less mercantilist Taiwan, or free trading Hong Kong and Singapore—which are richer than Korea? Whatever magic “special sauce” explains the success of all of the “Tiger economies”, it cannot be mercantilism.

Advocates of mercantilism often seem to lack a basic understanding of trade theory. For instance, they cite Korean import tariffs and export subsidies as if they were two pieces of evidence for mercantilism. They are not. A uniform 10% import tariff and a uniform 10% export subsidy roughly offset, netting out to free trade. One negates the effect of the other. These mercantilists think they have two good arguments, are like a child who thinks one plus negative one equals two. Sorry, it equals zero.

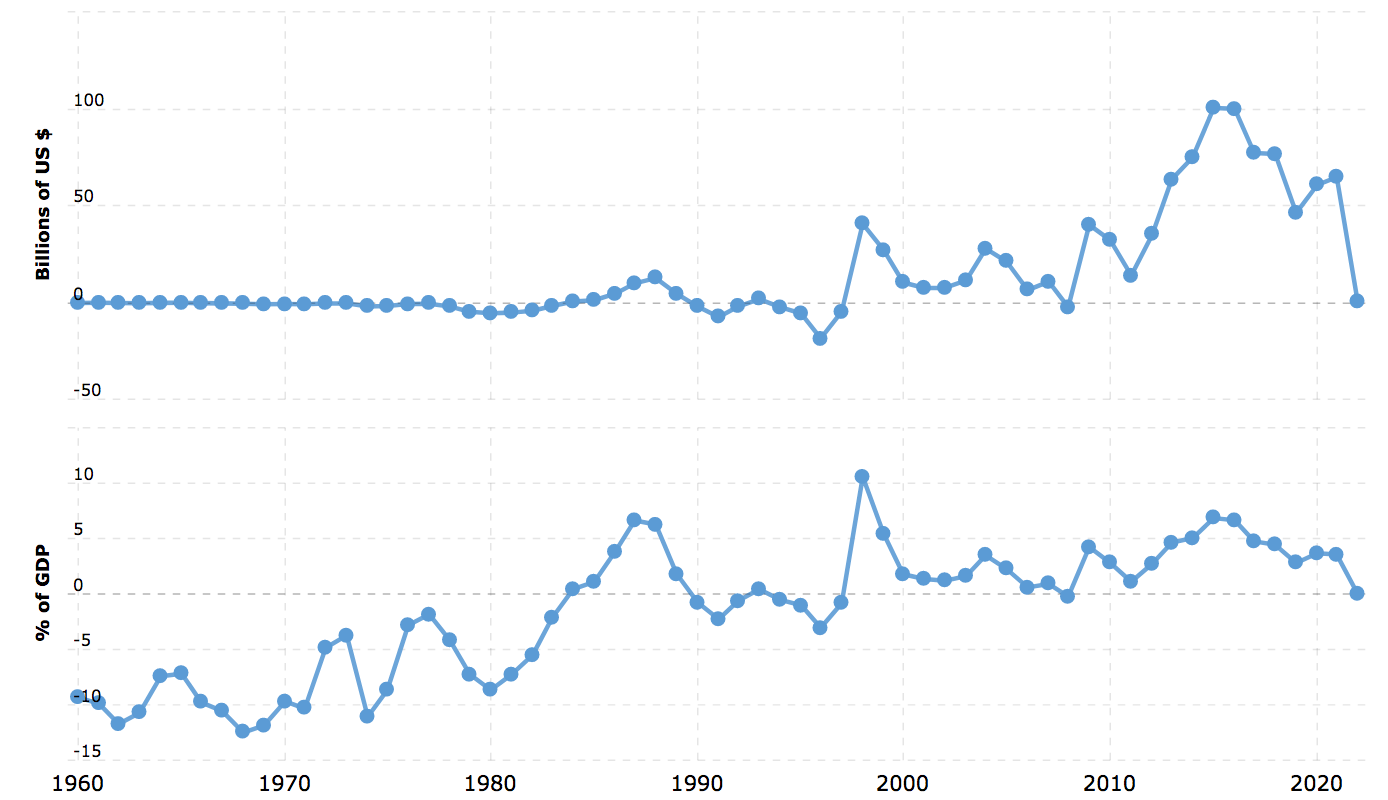

Mercantilists believe that trade surpluses are a sign of virility, ignoring the fact that the most successful major economy in world history (the US) runs trade deficits. More to the point, even South Korea ran fairly consistent trade deficits during its years of supercharged growth (roughly 1960-97.) Here is South Korea’s trade balance in dollars, and as a share of GDP:

Proponents of mercantilism often make comparisons between wildly different economies, where it’s hard to isolate any single factor as important, and ignore much more obvious natural experiments. Consider the following two facts:

A. South Korea has the fastest growing economy in the world since 1960. It has a mostly market economy, with significant government intervention.

B. North Korea was once richer than South Korea, but is now an economic basket case. It has one of the most interventionist policy regimes in the entire world.

I ask you, what rational person would look at those two facts and exclaim “Hmmm, from this data we can infer that the key South Korea’s relative success was its government intervention.”

I won’t say “always”, but almost everywhere you look a side-by-side comparison of countries favors the more free market model:

South Korea > North Korea

Taiwan > Mainland China

Hong Kong > Taiwan

West Germany > East Germany

Netherlands > Germany

Switzerland > Austria

Chile > Argentina

Botswana > Zimbabwe

Dominican Republic > Cuba

Ireland > Britain

Baltic states > Russia

UAE > Kuwait

Bangladesh > Pakistan

That’s cross sectional data. But what about time series evidence? China is often cited as a successful example of industrial policy. Perhaps to some extent it is. But even in the case of China, growth sped up sharply with free market reforms in the 1980s, and has slowed under Xi Jinping’s more interventionist approach. So is industrial policy the decisive factor? Or was it the unleashing of market forces on 1.4 billion entrepreneurial Chinese people?

Part 2: The sophisticated case for industrial policy

Now let’s consider a much harder problem. Are there good arguments for more finely tailored industrial policies, aimed at addressing certain perceived problems such as national security, winner-take-all markets, inequality, the environment, innovation, and a host of other complex issues? Brad DeLong concedes that the US has often lacked the state capacity to do effective industrial policy, but insists that we now have no choice:

Now, however, the United States has three overwhelming reasons to go all in on industrial policy. First, there is the looming disaster of runaway global warming, which requires action on a scale much larger than Al Gore correctly called for nearly a half-century ago. Second, there is the need to reorient the US economy from coastal finance and plutocracy to middle- and working-class prosperity nationwide. And, third, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a “no-limits” partnership with Russian President Vladimir Putin just before the latter launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since then, it has been clear that we are undergoing a historic geopolitical and geoeconomic transition in which, as Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, “defense … is of much more importance than opulence.”

Almost certainly there are plausible arguments for at least some industrial policies. But I suspect that economists tend to underestimate the complexity of the problems we face, and overestimate our ability to address these challenges with interventionist policies.

Before considering the foreign policy argument for industrial policy, let me remind readers of what can happen when experts go beyond their area of expertise. A few years ago, certain medical experts decided that they were also skilled social psychologists. They decided to withhold important medical information from the public, as they did not wish to create “panic”. (Actually, true panic is pretty rare—the public is far more rational than experts assume.) In any case, this backfired. Once the public realized the games being played, they lost a lot of trust in medical experts. Panic thrives on distrust. You avoid panic by creating an environment where officials tell the truth.

Now we have economists (including me) who pretend to be foreign policy experts. We are increasingly being told that war with China is likely, and we must change our economic policy to reflect that fact. I’m skeptical of the foreign policy consensus, but let’s leave that for another post. Here I’d like to ask the following question: What is the model?

Here’s a simple framework:

Expected damage = (probability of war) X (expected damage from a war)

Within that framework, you could imagine policymakers considering the trade-offs involved in various industrial policies. Thus the US oil embargo on Japan during the 1930s might have increased the probability of war with Japan, but reduced the expected damage if such a war did occur. The net effect would depend on whether the probability of war rose by a smaller or greater percentage than the expected damage from such a war.

Do you see economists constructing these sorts of models for evaluating trade policy with China? Neither do I. Too often they remind me of the medical experts who styled themselves amateur social psychologists.

In fairness, economists tend to do better than foreign policy experts. (Does the field of foreign policy even have a model?) Economists often prefer subsidies to trade wars, and that’s probably better from a national security perspective. Economists tend to favor high rates of skilled immigration from places like China and India, which also helps to strengthen the US in the global pecking order. So I’m not trying to single out economists—I’m even more skeptical of activist foreign policies such as nation building than I am of industrial policies. The world’s far too complex to be managed by experts.

Again, this doesn’t mean that all foreign policies are bad. (I happen to favor aid to Ukraine.) Perhaps one out of every ten foreign policy initiatives, or industrial policy initiatives, would provide a net benefit. The real problem is that we often don’t know which one of the ten will be effective.

In a world of complexity, I look for simple rules:

Wars of conquest are bad. Discourage them.

Have mutual defense agreements of like-minded nations.

Don’t try to do nation building.

Avoid nationalistic policies like trade wars. Commerce doesn’t prevent wars, but it makes them less likely (and more costly for the aggressor.)

Research subsidies might help, but by far the surest way of encouraging innovation is to attract talented people and give them an economic system where innovation is rewarded.

The low cost solution of environmental problems is Pigovian taxes.

The most effective solution for poverty is growth. Some redistribution can help, but it’s a distant second in effectiveness. Zoning reform helps the homeless more than “homeless programs”.

Don’t do regional policies. Italy has proved beyond any doubt that they do not work. Do sound economic policy, and hope that these policies either help the region, help people move to better regions, or both.

Here’s the basic problem. Neoliberalism produced the greatest reduction in global poverty ever seen, by far. But people get bored with success. Ambitious economists always want to look for the next new thing. And there’s always a reason to intervene. Even if neoliberalism “works”, we will always have economic problems. If neoliberalism is the dominant ideology, then it will get blamed for the remaining economic problems. With progress against poverty slowing in recent years, countries are turning back to previously rejected ideas:

And developing-world finance ministers are short of more than just money. What is remarkable is the lack of ideas—either home-grown or emanating from institutions based in Washington, dc—about how to get growth going again. Economic planning is back in vogue everywhere from Brazil and Cambodia to Kenya, with politicians claiming inspiration from China and increasingly America, too, in a little-noticed side-effect of President Joe Biden’s fondness for industrial policy. Their masterplans are often big on manufacturing ambitions, with all the tariffs and handouts you can imagine, regardless of the cost to international competitiveness. World Bank officials note that the governments they deal with are today more focused on boosting jobs than productivity, even if this means receiving investment that is less likely to pay off. . . .

Having watered down their “neoliberalism” and insistence on tough rules, Washington’s institutions have failed to come up with another big idea. So far, their best attempt has been “inclusive growth”, which covers matters such as jobs, inequality and sexism, along with more traditional subjects like trade and gdp. But it represents more of a wishlist than a rescue plan, and ultimately lacks rigour. Esther Duflo, a Nobel-prizewinning economist, is blunt: “We can be sure that a lot of [what the World Bank does] is useless.”

These developing countries may claim “inspiration” from China, but they are certainly not adopting Chinese policies.

One problem is a lack of resources. China is a high saving country. Most developing countries are not. Nor is the US, which has not stopped politicians from both parties from advocating socialized investment:

Top aides to President Joe Biden have been crafting a proposal to create a sovereign wealth fund that would allow the US to invest in national security interests including technology, energy, and critical links in the supply chain, according to people familiar with the effort.

The behind-the-scenes work by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and his deputy, Daleep Singh, mirrors — at least in spirit — a proposal floated Thursday by Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, who called for a government-owned investment fund to finance “great national endeavors” during a speech to the Economic Club of New York.

Larry Summers nicely describes the problem:

Summers said it was “hard to believe that setting aside lots of funds for unspecified investments made in unspecified ways, where you don’t even know what it’s going to be called, is a particularly responsible, kind of proposal.”

And where will the funds come from? The Economist points out that entitlements are crowding out public investment:

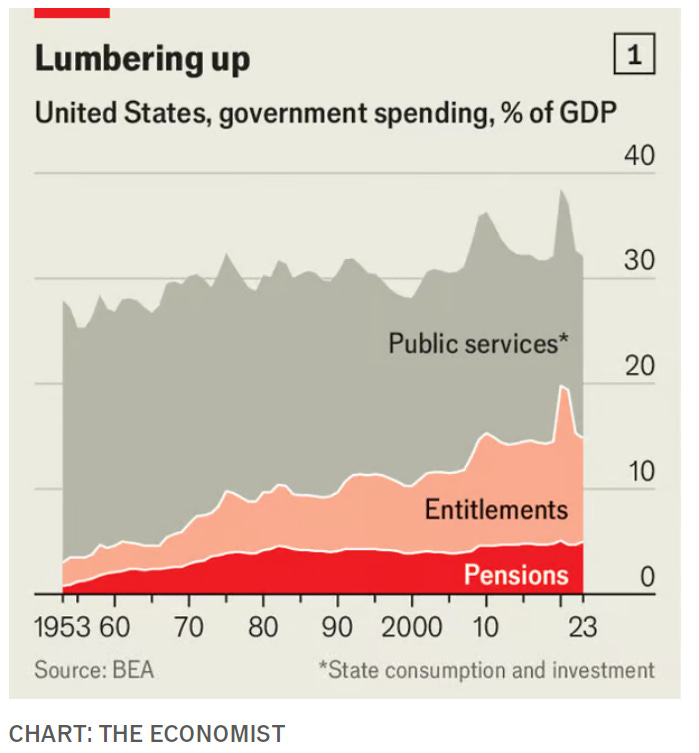

In the early 1950s we estimate that state spending on public services, including everything from paying teachers’ salaries to building hospitals, equalled 25% of the country’s GDP (see chart 1). At the same time, entitlements spending, broadly defined, was a small line item, with outlays on both pensions and other sorts of welfare equivalent to about 3% of GDP. Today the situation is very different. The American government’s outlays on entitlements have swelled and spending on public services has crashed. Both now equal around 15% of GDP.

Another article in The Economist points out that the EU faces the same problem.

I started this section with a quote from Brad DeLong, one of the most thoughtful advocates of industrial policy. So where do he and I disagree?

I could imagine there are many areas where we might actually agree on policy. I favor trade sanctions on Russia, a carbon tax to address global warming, more high skilled immigration to help our tech industries.

But even in that limited list, there are warning signs. Back in early 2022, many of the same pundits that now advocate industrial polices were telling us that the Russian sanctions were highly effective, and would seriously damage their economy. These predictions turned out to be completely false. We were told by the same experts that the shutoff of Russian gas would severely damage Europe’s economy. If they can’t even get those two predictions right, how can we have confidence in their much more complex policy proposals?

After all, sanctions ought to be one of the easiest policies to adopt. But we now discover that Germany continues to supply large amounts of industrial goods to Russia, albeit funneled through central Asia. DeLong mentions China’s support for Russia, but you can argue that India has been an even bigger factor, as its imports of Russian oil have surged far more than have Chinese imports of Russian oil. And our foreign policy establishment views Germany and India as friendly nations. Market forces have a way of getting around even the best intentioned policy constraints.

An excellent recent article in The Economist nicely explains the problem. They start out with an anecdote about how US bombers destroyed most of Germany’s ball bearing production in 1943. This was supposed to cripple their war machine. Unfortunately, it had almost no effect. Experts continually underestimate the importance of substitutes:

In a book to be published next year, Mark Harrison and Stephen Broadberry, two British scholars, use a theory first set out in the 1960s by Mancur Olson, an economist, to explain this paradox. The concept of a strategic commodity, they argue, is an illusion.

A good is often described as “strategic”, “vital” or “critical” when it is thought to have few substitutes. America and China have strategic reserves of petroleum, because their leaders think oil cannot easily be replaced, at least in the short run. Some minerals are deemed critical because you cannot build a viable electric car without them. But Olson reckoned very few goods, if any, are truly strategic. Instead, there are only strategic needs: feeding a population, moving supplies, producing weapons. And no amount of pounding, literal or figurative, seems able to alter the target countries’ ability to meet those needs, one way or another.

Shipbuilding capacity, rare earths, natural gas, computer chips, etc., etc. We are continually being presented with an ever larger list of essential goods, with dire warnings of what could happen in a future emergency. I’m not suggesting that these concerns are completely groundless, but recent history suggests we should be a bit skeptical.

Now consider this part of DeLong’s claim:

reorient the US economy from coastal finance and plutocracy to middle- and working-class prosperity nationwide.

Sounds nice, doesn’t it? But what’s actually going on here? In my view, intellectuals were panicked by the rise of Trump and looked for scapegoats. Neoliberalism made a convenient target. But the Trump/Biden tariffs have done precisely nothing to reduce our trade deficit or revive manufacturing. And it’s not even clear that the Rustbelt explains the rise of Trump. Lots of my neighbors in Mission Viejo are voting for Trump, and it’s not because jobs were lost in Cleveland and Buffalo. (I suspect it’s some combination of immigration, inflation, distaste for wokism, and the fact that Trump hates the people they hate.)

Be careful what you wish for. If you set up a highly effectively industrial policy, it might later be highjacked by the authoritarian nationalist right to boost their wealth and power and crush their enemies. Sound far-fetched? Check out Hungary.

The sad truth is that policymakers do not know how to fix regional problems. For decades, Italy spent lavishly to fix its south and failed. Germany spent a lot of money and built some nice stuff in the east, but there is increasing evidence that its regional policies have also failed (albeit perhaps not as badly as in Italy.) I suspect that if we knew how to fix the problems in West Virginia or Louisiana, we would have already done so. (How about free bus tickets to Dallas or Houston?) In contrast, I think we do know how to fix Illinois (be more like Indiana.)

I am not impressed when someone tells me that a small homogeneous country has less inequality than the US. I am impressed by the fact that almost every single ethnic group in America is more successful than the equivalent ethnic group in their home country.

In the 1960s, there were fears that the US would be overtaken by the Soviet Union. I can still recall the late 1980s, when pundits insisted we needed an industrial policy to avoid being overtaken by Japan. A decade later, those fears looked groundless. Indeed that realization probably explains why the late 1990s was “peak neoliberalism”. Then we had the Islamist terrorism hysteria of the 2000s. The crash of 2008 was attributed to “unbridled capitalism”, even though it was actually due to a monetary policy that allowed a big drop in NGDP. In the 2010s, Chinese exports were blamed for manufacturing job losses that were mostly due to automation. Now the fears are focused on Chinese military power. I have no idea what the threat of the 2030s will be, perhaps something related to AI.

I am not suggesting that these previous worries were completely groundless. The Soviet Union was a real threat, as was Islamic terrorism. There is certainly reason to be concerned about the possibility of a Chinese move against Taiwan. Rather, I’m suggesting that many of these previous fears were clearly exaggerated. (With Islamic terrorism, I plead guilty.)

Right now, the US economy is the envy of the world. Before we replace free markets with an industrial policy, we might wish to compare upside and downside risks from interventionism. Given that our living standards are currently the highest in the world (at least for countries of more than 10 million), in which direction are the risks the greatest?

Summary:

In the previous post, I showed that economists really do know some useful things, even some useful things that are non-obvious. For the most part, those reflect relatively simple applications of basic economic theories like supply and demand and comparative advantage.

Yes, those simple models do not address all of our problems, some of which are highly complex. Unfortunately, we aren’t very good at constructing solutions to complex problems. Often, we must accept that there are problems for which we don’t have a good solution, or for which the only solution is long run cultural change (here I’m thinking about regional problems like Sicily, East Germany, West Virginia and Louisiana.)

But that’s no reason to be despondent. Cultural change can happen more quickly than you might think. You can find many places that are doing better than cultural pessimists expected. (Recall when Catholicism was viewed as a backward religion—now Ireland and Poland are booming.) And if Deirdre McCloskey is correct, free markets can actually engender positive cultural change.

Do the simple things that we know or have strong reason to believe will work, and steer clear of complex policy regimes for complex problems.

"In the 1960s, there were fears that the US would be overtaken by the Soviet Union. I can still recall the late 1980s, when pundits insisted we needed an industrial policy to avoid being overtaken by Japan."

In the early 1980s, I moved out of research and into corporate work doing mainly regulatory affairs and drug safety in the biopharma industry. I was at an annual meeting of the biotechnology group where I worked and most of the speakers were covering a wide range of international issues (as an aside, I recommended we invite a very young Paul Krugman who came and gave a nice talk on international trade and economics). Clyde Prestowitz spoke at the meeting and at that time he was at the Commerce Dept in the Reagan administration and an outspoken "worrier" about Japan and gave a very gloomy talk about how Japan's industrial policy was endangering the US. While Japan was buying up a lot of US real estate, the economic takeover never happened. Nor is it like to happen with China either.

One more anecdote, though the actual reference must be somewhere in my paper archives. Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry was busy trying to set policy for companies. The relatively small motorcycle company, Honda, was starting to manufacture automobiles and the recommendation was for them to leave this sector to the then giants, Datsun and Toyota. The CEO ignored that advice and of course Honda became one of the premier auto manufacturers in the world.

I’ll continue shouting this from the rooftops wherever I read someone repeating that the sanctions on Russia are tough. They’re not. They’re highly targeted and circumscribed. If the phrase “secondary sanctions” doesn’t appear in a discussion of sanctions, then I know the author is unaware of by far the strongest tool in our sanctions arsenal. We are only gradually and belatedly beginning to use secondary sanctions.

https://www.ft.com/content/be8f3264-ac16-4fd9-b1ba-4e5e6fba466b