Moving toward NGDP targeting

and away from interest rate targeting

In a recent Discourse column, Patrick Horan made the case for a more flexible interest rate targeting regime:

Economist Scott Sumner has argued that with modern technology, there is no reason why the FOMC could not vote on possible changes to the interest rate target much more frequently. For example, FOMC members could email their preferred targets every business day, and the median vote would be the new target for that day. Members could also vote to the nearest basis point. Suppose a new unemployment report shows that unemployment ticked up, but only very slightly. Rather than wait for the next FOMC meeting, a member could vote for a small cut—say, 5 or 8 basis points—the very next day to add liquidity to the economy.

I’ve also argued that the Fed should abolish its program of paying interest on bank reserves. Under the pre-2008 corridor system, the monetary base was more than 98% currency, and monetary policy operated by using open market operations to directly change the size of the base, with the goal of moving the fed funds rate to a specific target.

Before making my case, let me emphasize that monetary policy can be somewhat effective even when limited to infrequent quarter point rate adjustments, and can work when the central bank pays interest on bank reserves. There may even be some modest efficiencies of using a floor system with lots of liquidity (although I’d argue they are relatively small.)

A Fed that moves every 6 weeks in quarter point increments can still do a certain amount of “fine tuning” through communication. For instance, if bad news hits right after a rate decision, Jay Powell can give a speech hinting at how the Fed is likely to respond at the next meeting.

But even if the current system is workable, I worry that it leads to an over reliance on interest rate targeting, which I view as vastly inferior to NGDP forecast targeting. Interest rate targeting makes it more likely that the Fed will fall behind the curve.

Under the current system the Fed is very reluctant to change course, as doing so would seem to imply that the previous rate path had hurt the economy. For instance, when the economy plunged into a second wave of depression in late 1937, the Fed was reluctant to reverse the reserve requirement increases that it imposed in early 1937, fearing such a reversal would give the impression that the previous move was a mistake. If we make the fed funds target more like a market price, moving up and down each day by a few basis points as new data comes in, then there is no longer any embarrassment from changing course.

The payment of interest on bank reserves has the effect of increasing the demand for base money, which is a contractionary policy. Thus it is certainly possible to raise and lower IOR as a tool of monetary policy. Just as open market operations affect the value of base money by impacting its supply, IOR affects the value of base money by impacting its demand.

Again, the problem lies elsewhere. The use of IOR gives the impression that interest rates are equivalent to monetary policy. People begin to believe that higher market interest rates represent tighter monetary policy, which is not necessarily true. I suppose you could adjust IOR up and down each day as a tool to control NGDP, but as a practical matter we are more likely to get to NGDP targeting if we completely abandon interest rate targeting. You cannot target both interest rates and NGDP expectations, at least over the same time frame.

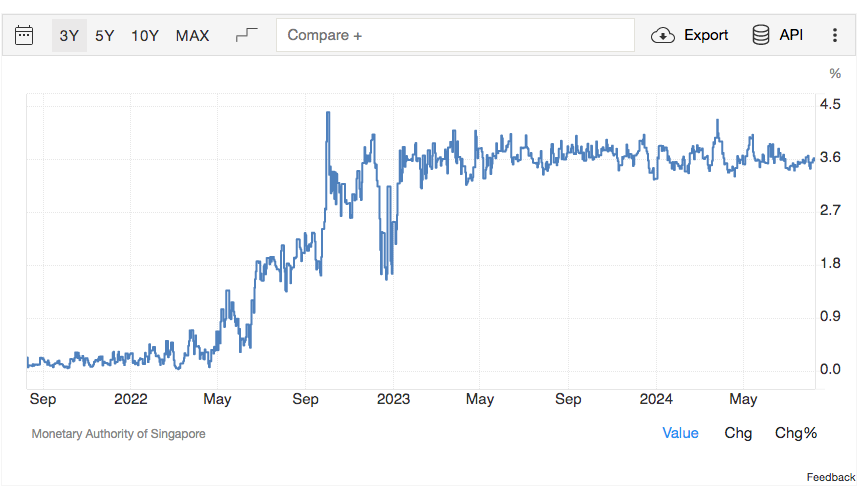

Imagine a central bank that is targeting something other than interest rates. Under that sort of policy regime, the overnight interest rate would move up and down each day, reflecting shifting conditions in the credit markets. Here’s the overnight interest rate in Singapore, where the central bank targets the nominal (trade-weighted) exchange rate:

That sort of high frequency volatility is what short-term interest rates would look like under an efficient monetary regime. I do not recommend an exchange rate target for the US, rather I prefer that the Fed target the market forecast of NGDP, using open market operations. Do that and then let the free market set interest rates.

Purists will insist that it is technically possible to do NGDP targeting with IOR and quarter point increments. That’s true. But the outcome is likely to be worse than under a regime where interest rates are not being targeted at all. Almost inevitably, the targeting of interest rates becomes a sort of obsession, an end in itself, and policymakers lose sight of the actual goal of policy.

During late 2008, the Fed was distracted from stabilizing NGDP by a misguided belief that they needed to proceed methodically in cutting interest rates. If they had focused on stabilizing NGDP expectations, they would have allowed rates to fall sharply. They knew they needed to inject a lot of liquidity, and they did so. The imposition of IOR was based on the mistaken belief that they also needed to target interest rates. They did not.

In late 2021 and in 2022, the Fed raised rates much too slowly, again based on the mistaken view that they needed to move methodically. You don’t need to stabilize interest rates; you need to stabilize NGDP expectations. Ironically, interest rates are probably more stable over the medium term if the central bank allows high frequency short run volatility as part of a regime that targets NGDP. That’s because stable NGDP growth tends to also stabilize the natural rate of interest.

If the Fed were to allow the fed funds rate to move up and down like a market price, then policymakers would begin to look elsewhere for stability. And what better variable to stabilize than the market forecast of future NGDP?

To summarize, abolishing IOR and moving to a highly flexible fed funds rates doesn’t magically get you to NGDP targeting. But it’s a nice first step, which creates an environment where targeting NGDP market expectations seems like the natural next step.

"Ironically, interest rates are probably more stable over the medium term if the central bank allows high frequency short run volatility as part of a regime that targets NGDP."

this concept of taking lots of short run micro actions to smooth out the target variable is familiar to anyone in STEM. it really is just a dynamic control systems problem.

this phenomenon is also self evident in portfolio rebalancing, delta hedging, and high frequency trading.

regulators are just not scientific thinkers despite the Fed's best efforts to be structured like a academic research institution.

In the analyst Victor Shvets’ interesting take, Arthur Burns, in having presided over the stagflationary 70s, haunts his successors for demonstrating that the better course is to be data-driven and behind the curve. While this means its policy moves tend to increase volatility, it’s an acceptable price to pay to avoid a comparison with Burns.