Discover more from The Pursuit of Happiness

As you’d expect, Alex Tabarrok and Tyler Cowen made lots of good points in their recent debate over the cause of the Great Inflation. (They specify the 1970s inflation, but I’d include all of 1966-81.) At times it was a bit difficult to sort out exactly what was being contested. For instance, consider the following three claims:

The Great Inflation doesn’t happen without the federal government as a whole deciding that they wanted to have lots of stimulus.

The Great Inflation doesn’t happen without the US decision to abandon the (international free market) $35/oz. gold price peg in March 1968.

The Great Inflation doesn’t happen without the Fed deciding to print money at a much faster rate than the economy was growing.

I feel very, very, very strongly that all three of these claims are true. I have no reason to believe that either Tabarrok or Cowen disagrees with any of these three claims. (They certainly agree with at least some of them.)

Here’s an analogy. Someone decides he wants to murder someone. He puts a bullet in the chamber of his gun. He pulls the trigger. All three steps were necessary to make it happen. The decision to kill is like the decision to stimulate the economy. Putting the bullet in the gun is like going off gold. Printing lots of money is like pulling the trigger. If I’m right, then I don’t think it would make much sense to quibble about what was the actual cause of the Great Inflation. It’s a complex process.

Again, they may well agree, but some readers may get lost in the weeds.

Other portions of the debate were more interesting, with each side winning a few points, in my view. I’ll focus on areas where I disagree:

TABARROK: Let’s sum up, let me give you my bottom line, which you won’t agree with, but I’ll give you my bottom line. That is that, in the 1960s, in the 1970s, the Keynesian economists abandoned things like balanced budgets, they abandoned the mythology of balanced budgets and they were proud of it. The problem is that abandoning balanced budgets doesn’t lead to countercyclical fiscal policy and economic stabilization, but rather to political business cycles, bigger governments, and perpetual deficits. That’s my bottom line take from this, Tyler.

I don’t agree. The budget deficits during the 1960s and 1970s were not very large as a share of GDP, and played essentially no role in the inflation process. In fiscal 1968-69, the peak year of the Vietnam war, we ran a surplus. Deficits got worse in the 1980s, but inflation came down. In fairness to Tabarrok, support for fiscal deficits could correctly be viewed as part of a Keynesian stimulus mindset, which spilled over to monetary policy. Indeed, elsewhere in the debate he makes that point:

TABARROK: Now we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s go back and look at the beginnings of inflation. I actually would blame inflation on the Keynesians. I would blame it on the Kennedy Johnson tax cuts of 1962 and 1964. Now, not because these tax cuts themselves were inflationary, but rather because these tax cuts were really the first truly Keynesian fiscal policy in US history.

Cowen is more supportive of deficit spending:

COWEN: You would agree, though, it’s a good thing that we run budget deficits, though admittedly, not at current levels, which I think are close to 6 percent of GDP in 2024, because you create another safe asset, right?

TABARROK: No.

COWEN: David Beckworth’s point. There’s this shortage of safe assets. The world needs more of them. There’s not anything else you can use. Not at the moment.

TABARROK: We can create safe assets.

Here I side a bit more with Tabarrok. It is probably optimal to have small budget deficits, so perhaps Tyler and I don’t actually disagree. But I wouldn’t make them larger than suggested by public finance “tax smoothing” considerations, merely to provide more safe assets. The world doesn’t “need” them.

They debate whether it was necessary that we left the gold standard. Cowen points to the unstable value of gold, and Tabarrok replies:

TABARROK: No, the increase in the volatility of the price of gold, that was endogenous, that was caused by going off the gold standard.

COWEN: At first but later on it was China, other demands, right?

TABARROK: Maybe. Moreover, the reason why Bretton Woods came under attack was that all these other countries, including France, which were holding dollars, they realized that the US government is inflating. The US government is destroying the value of the dollars.

COWEN: They also demanded that we inflate. They need more dollars.

TABARROK: I don’t see it that way. I don’t see it that way.

I’m more with Tyler on the gold stability question, although Alex is right that monetary instability contributed to this problem. But I’m with Tabarrok on Bretton Woods not forcing us to inflate, a claim that mixes up real and nominal factors. Countries can accumulate dollar assets by exporting goods. Adding US inflation to the picture boosts nominal reserves but has little effect on real reserves.

TABARROK: Let me ask then, Tyler, what were the causes of the inflation of the 1970s?

COWEN: I think there’s several causes. First, in Scott Sumner’s terminology, the Fed let nominal GDP grow at too high a rate. You could rephrase that in terms of the money supply.

TABARROK: What do you mean the Fed "let"? I mean the Fed made nominal GDP grow too quickly.

COWEN: It’s jointly determined by the private sector and the Fed given political constraints and acting in cahoots, so to speak. NGDP is growing at way too high rates or you could rephrase that in terms of the monetary aggregates. M2 also being jointly determined with the private sector, to be clear, but mostly it’s the Fed, but then you have, on the fiscal side, the dollar is simply not being backed the way it used to be. Of course, it’s going to end up being worth less.

Exactly how you get there, you could say, well, fiscal theory of the price level is weak on that, I would agree, but it’s what you should expect. I also think it was a good thing we got off gold when we did. I’m not upset about that, even though I clearly would admit the concomitant inflation was bad for the economy.

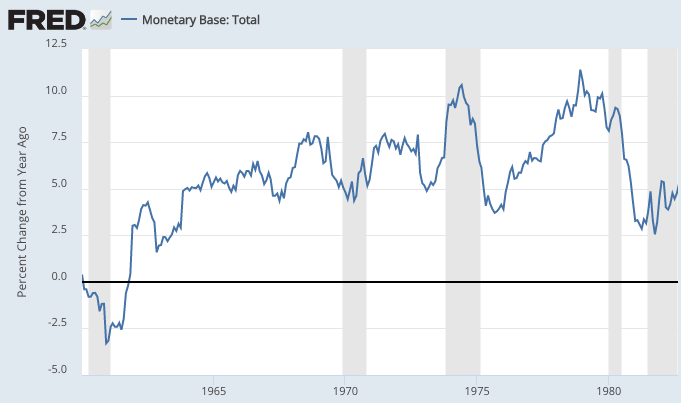

Obviously I’ll agree with Cowen, as he cites my name. And I like the way he notes a problem with the FTPL. But I also like the way Tabarrok challenged him on the use of the term “let”. It’s not even necessary to cite M2, or fiscal deficits. The Fed printed base money at a much faster pace than the real demand for base money was growing. Don’t make it complicated.

Here’s the growth rate of the base:

(Base velocity also trended higher, exactly as you’d expect during a period of rising inflation.)

The conversation is much longer, and I agree with most of the stuff that I did not discuss. In particular, they made some goods points about the Fed’s lack of independence. That got me thinking about the relationship between previous inflation and future Fed independence. They both noted that voters have become quite allergic to inflation, more than many economists expected.

I wonder if that means that periods of high inflation are followed by periods of Fed independence? Because inflationary policies become temporarily discredited, there is a period of time where the central bank has a freer hand to pursue its objectives. That happened under Volcker and Greenspan, and perhaps we’ll get a similar period until memories of 2021-22 fade away.

Slightly off topic, this caught my eye:

COWEN: The 1970s is an especially interesting decade to me, because it seems to be the time when we Americans did everything wrong. Productivity growth goes down the toilet, inflation is high, there’s a lot of political disorder, a president has to resign.

I view this as a sort of golden age, when the rule of law still applied and corrupt presidents were held to account. We did at least one thing right.

Today . . . well, you know my views.

Subscribe to The Pursuit of Happiness

Nostalgia for the Neoliberal Era

I find it rather odd to debate what caused the Great Inflation. The answer is clearly loose monetary policy? People understood this at the time and for a long time afterwards – which absolutely helped pave the wave for Fed independence. The more interesting question is why was monetary policy so loose...

I'm not sure I understand your point #2. Are you arguing that the Great Inflation was caused by the gold peg change in 1968? Or that the Great Inflation caused the gold peg to change?

It’s really not fair or accurate to say, as Tabarrok did, that people were proud to abandon balanced budgets... Here’s LBJ in 1968:

"One way or the other we will be taxed. We can choose to accept the arbitrary and capricious tax levied by inflation, and high interest rates, and the likelihood of a deteriorating balance of payments, and the threat of an economic bust at the end of the boom.

Or, we can choose the path of responsibility. We can adopt a reasoned and moderate approach to our fiscal needs. We can apportion the fiscal burden equitably and rationally through the tax measures I am proposing."

Unfortunately, people chose inflation and (eventual) high interest rates rather than higher taxes!

I also don’t quite understand Tabarrok’s point about gold stability. Volatility increased by going off the gold standard? Well, yeah, obviously? If the price of gold is fixed, it won’t be volatile…

Thanks for pointing this out. I do wonder why the oil shock(s) are not mentioned. I lived through that period of time and remember at one point that there were odd and even days that you could gas up depending on the last digit of your license plate. Oil is feedstock for a great many items and the dramatic price increase rippled through society. Volker's crushing of inflation benefited those of us who had no debt and put all our money in high yield insured savings accounts. It was an interesting time to be sure.